The Uzbeks and the Qazaqs

|

The Uzbeks and the Qazaqs

|

|

This is a Temporary PageThe steppes to the north of Transoxiana and the Caspian and Black Seas became known as the Qipchaq Steppes during the Golden Horde period, named after the Khan of the Qipchaq, Batu. It is sometimes referred to by its Persian name, the Dasht-i Qipchaq. Just like Khorezm, the settled part of Toktamish's former province had been devastated by Timur. Ibn Arabshah, writing shortly after Timur's death described how: " ... the cultivated part of Desht became a desert and a waste, the inhabitants scattered, dispersed, routed and destroyed, so that if anyone went through it without a guide and scout, he would certainly perish, losing the way ...". The once flourishing caravan route from Khorezm to Crimea was empty: " ... nothing ranges there but antelopes and camels".

The Qipchaq steppes range from Central Europe to Mongolia.

"He was an able padishah, shepherd of the flocks, and God fearing. His highness ... possessed an eminence among kings, because moral virtues achieved by no one [else prevailed] in his governance and reign. .. Abu'l Khayr Khan was distinguished among preceeding and following kings especially by great magnanimity."Under Abu'l Khayr's rule many of his nomadic tribal supporters migrated eastwards into the Syr Darya valley – not just those from within the Shaybanid-Uzbek Horde, but many Mangits and other tribes from the eastern Noghay Horde. However Abu'l Khayr's growing empire was brought to a halt by the Kalmuks, eastern Mongols from the Altai, who invaded his emerging Uzbek Khanate in 1457, plundering and devastating the north bank of the middle Syr Darya. This severely weakened the new regime and many of the nomad clans that formerly supported Abu'l Khayr deserted him. Over the next decade they migrated eastwards, settling on lands offered to them by the Khan of Moghulistan, in the Chu and Talas valleys, located in the centre of southern present-day Kazakhstan. Following their separation from the Uzbek Khanate, these nomads became known as Qazaqs (meaning adventurers or rebels) or Kyrgyz-Qazaqs, making this division one of great historical importance, given the extent of the territory that they would soon occupy. The Qazaqs subsequently divided themselves into three separate confederations located on their own pasturelands in the steppes: the Junior or Younger Juz or Horde occupied the region between the lower Ural River and the Sarysu, the Middle Horde the northern steppes between Aktyubinsk and Semipalatinsk, and the Senior Horde the steppes between Turkestan and the south of Lake Balkash. We have only sketchy details of Khorezm following its annexation in 1430. Abu'l Khayr appears to have installed a Shaybanid prince to rule his new province, Timur Shaykh, a grandson of Arabshah ibn Fulad with a direct line of descent from Jöchi. He, and particularly his descendants, would become one of Khorezm's important ruling families, known as the Arabshahid dynasty. Khorezm too experienced a gradual influx of Uzbek tribes belonging to the Shaybani Horde, some even venturing into the Turkmen territories along the east coast of the Caspian Sea, including the Mangishlaq peninsula. The arrival of the Uzbeks would pose a major challenge to the independence of Khorezm's Turkmen population and would be followed by almost half a millennium of ethnic conflict. The reign of Timur Shaykh was brought to a sudden end during a skirmish with Kalmuk raiders. The new Uzbek Khanate was faced with the problem of deciding who should succeed him - at the time of his death he was childless and had no younger brothers. Fortunately they discovered that his eldest wife was three months pregnant and when she gave birth to Yadigar, a son, he was enthroned as the figurehead Khan of Khorezm. Obviously tribal Begs were also installed to rule the province until Yadigar reached manhood. He eventually had four sons of his own, three of whom would become future Khans of Khorezm. His eldest son, Burge Sultan, provided valuable assistance to Abu'l Khayr by conquering a large part of Transoxiana, and also assisted the Qongrats in their feuds with the Mangits. In 1468 Sultan Husayn Bayqara requested help from Abu'l Khayr in his bid to seize the throne of Timurid Khurasan, but by then the Khan was suffering from palsy. Abu'l Khayr was killed a few months later in a battle with the Kyrgyz-Qazaqs, who he was trying to forcibly bring back into the fold. His son was beheaded later that year in the same dispute. This left a vacuum at the heart of the Uzbek Khanate and a subsequent power struggle, partially filled by Yadigar Khan who extended his rule over some of the Uzbek tribes beyond the boundaries of Khorezm. Following the death of Abu Said, Sultan Husayn Bayqara gained control of Khurasan in 1469, although another Timurid Sultan took nominal control of Transoxiana. On the death of his father some years later, Burge Sultan became the new Khan of Khorezm but was soon assassinated by Abu'l Khayr's 17-year-old grandson, Muhammad Shaybani. Burge's younger brother Abulek took the throne and ruled for sixteen years despite an apparently very un-Khan like meek and inoffensive manner. Abulek was eventually followed by his younger brother, Amenek, who sired six sons, five of whom would eventually become Khans of Khorezm.

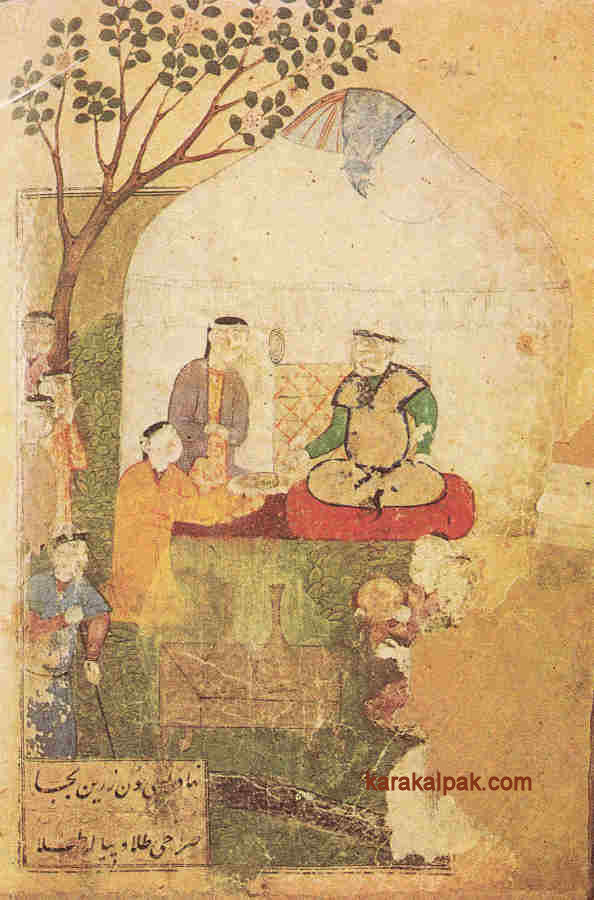

Miniature painting of Shaybani Khan.

|

|

Shaybani was now keen to extend his conquests to Khorezm, still a dependency of the Shah of Khurasan, Husayn Bayqara. It seems likely that Khorezm

was still ruled by Amenek Khan – we are told by Munis that he was on the throne when Shaybani Khan conquered Transoxiana. In 1505 Shaybanid forces

led by Shaybani's brother Mahmud Sultan laid siege to Urgench, which was defended by its governor with strong Turkmen support. The city was only

taken after a 10-month siege, suggesting that it had been extremely well fortified and defended at this time.

The next logical conquest for Shaybani was Khurasan especially as its ruler, Husayn Bayqara, had only just died in Herat. He took the province in

1507 without great resistance or bloodshed. In 1509-10 the Uzbeks moved on to invade Kerman. Within the space of a few years Shaybani had created

a new Uzbek Empire that was becoming the foremost power in Central Asia.

|

However the Uzbeks had come face to face with the newly independent Safavid dynasty in Persia, which had finally overthrown the Turkmen Horde of the

White Sheep, ending four and a half centuries of Turkic and Mongol rule in that region. The Safavids were originally the leaders of a radical Sufi

order that had sprung up in the Azerbaijan city of Ardabil during the 14th century. Having adopted Shi'a Islam in the mid-15th century their

religious philosophy became extreme, demanding that their new faith should be imposed by force of arms. Having built up a fanatical following, the

Safavids took control of Tabriz in 1501 and proclaimed their 14-year-old leader, Ismail Safavi, the Shah of Iran - even though at the time they

controlled little more than the province of Azerbaijan. Over the next decade they progressively gained control of the whole of Persia and began the

process of converting a nation of Sunni Muslims into Shi'ites.

In order to recreate the former integrated state of Persia, the Safavids were keen to win back Khurasan and Kerman from the Uzbeks. Shaybani rejected

Safavid territorial and hereditary claims to the region and challenged the Shi'ite leaders of the new regime to leave earthly matters to the Mongols.

He insulted Shah Ismail by sending him a begging bowl, inviting him to resume the career of his Sufi dervish ancestors. The Shah was said to have

replied that he was indeed a dervish and would therefore come with his army to the sanctuary of Meshed in central Khurasan. While Shaybani was

diverted by an attack on his rear by the Kyrgyz, the Shah of Iran fulfilled his promise and invaded Khurasan, first taking Meshed. Shaybani

meanwhile waited in the Uzbek stronghold at Merv. The Safavid attack came in November 1510 and after being initially repulsed the Persian forces

feigned withdrawal. Shaybani Khan gave pursuit and was killed in the ensuing battle and his Uzbek army was routed. It was a momentous defeat since

at long last the army of a sedentary regime had finally overcome the army of a nomadic regime. Tradition has it that the Persian Shah celebrated

his victory in true nomadic style by making a drinking cup out of Shaybani Khan's skull.

|

|

The death of Shaybani could well have been the end of the nascent Uzbek State. Having taken Khurasan, the Persian army swept north to occupy Khorezm

and Transoxiana. The Persians sent out an invitation to Babur, the dynastic heir of the Timurids. The capable Babur had taken the throne of

Ferghana at the tender age of fourteen and had subsequently annexed Samarkand, only to be evicted from his territories by the Uzbeks. He responded

by invading Afghanistan in 1504, which effectively left him exiled in Kabul. Babur returned to Transoxiana in 1510, where the population initially

welcomed him with open arms. However, the Turkic-Mongol populations of Samarkand and Bukhara were mainstream Sunni and did not take kindly to the

minority Shi'ite Persian Muslims. It did not take long before Babur was being criticized for dealing with heretics. Encouraged by the growing

religious disturbances, the Uzbeks returned from Tashkent to Transoxiana in 1512 and defeated the Persian army at a major battle at Ghujduvan, north

of Bukhara.

Rather than appoint an overall ruler of Khorezm, the Persians had installed three darughas, or city governors, to rule Khiva and Hazarasp,

Urgench, and the new town of Vazir. The princes of the former Arabshahid dynasty led the resistance against the new rulers, especially the two

Sultans, Ilbars and Balbars, both sons of Burge Sultan. As in Transoxiana, the princes exploited the dislike of the profoundly Sunni populations

of Khorezm for the heretical occupying Persian forces. The initial revolt began in Vazir, with the local nobles closing the gates of the city and

massacring the Persian rulers within. Ilbars was proclaimed Khan the following day. Three months later Ilbars Khan captured Urgench and then

rallied the other royal princes for an attack on Khiva and Hazarasp. Although Balbars legs were crippled with paralysis he was nonetheless a

brave warrior who participated in the fighting.

Ilbars (1511-1517) became the Khan of the newly independent Khorezm, ruling from his capital at Urgench. He is often referred to as the Khan

responsible for establishing a new Khorezmian dynasty, termed either Shaybanid or Arabshahid, neither of which are truly correct. Though descendants

of the original Shaybanid Horde, their family line was different to that of Shaybani Khan, who re-established Uzbek power in Central Asia - because

of inter-clan rivalries they had not participated in Shaybani's campaigns. At the same time we have already seen that the Arabshahid dynasty dates

from 1430. Ilbars' achievement was to restore legitimate Arabshahid rule. Under his regime another wave of Uzbek tribes began to migrate into

the Khorezm oasis from the eastern Qipchaq Steppes.

During his reign Ilbars raided northern Khurasan to incorporate the oases of Merv, Nisa, and Abiward into Khorezm and also subdued the Turkmen tribes

living in Mangishlaq and Balkan. The repetitive raiding of neighbouring territories would become a routine affair for Khorezmian rulers over the

coming centuries and would lead some historians to label Khorezm a "brigand state". According to usual practice the Khanate was divided into

appanages that were shared out among all the male members of the ruling clan. It operated less like a State and more like a confederation

of nearly independent principalities under one nominal ruler whose power over the other members of his family was sometimes slender. A second Uzbek

Khanate was formed in Transoxiana by a different branch of the Shaybani clan with Samarkand as the official capital, and Bukhara as the second royal

city. It was headed by the Khan of Bukhara.

Following the eastward migration of many tribes from the Noghay and Uzbek Hordes, the residual Golden Horde in the western Qipchaq Steppes was not

only weaker but was in the process of re-crystallizing into three new power centres. During the middle of the 15th century various Turkic-Mongol

tribal leaders established the Khanate of Crimea to the north of the Black Sea, the Khanate of Khazan in the territory of the old Bulghar kingdom

on the middle Volga, and the Khanate of Astrakhan on the northwest Caspian. Their leaders were Mongol by descent but their populations were Turkic

and Islamic. The Russians had suffered several centuries of persecution by their Tartar neighbours, but were now emerging under Ivan the Great

as a powerful nation. When the Golden Horde army approached Muscovy in 1480 they were surprised to be opposed by a strong and professional army

and decided it might be wise to avoid a confrontation. Russia subsequently entered into an alliance with Crimea against the Golden Horde and in

1502 the Khan of Crimea attacked and destroyed its capital city of Saray. After just over 250 years of rule, the last of the great Mongol Hordes

was finished.

It truly was the end of an era. Although many leaders would claim to rule under Mongol authority for centuries to come, the Turks were essentially

back in control of Central Asian affairs. At the same time, the Shi'ite conversion of Iran had introduced a cultural barrier, isolating Khorezm and

the rest of Central Asia from the orthodox Sunni populations of western Inner Asia.

But the biggest revolution was taking place a long way away from Khorezm. After several attempts, the Portuguese finally found a sea route to India.

In 1498, Vasco de Gama reached Kerala after sailing around the Cape of Good Hope. There would now be a much more economic and secure way of

transporting merchandise from India and Asia to Europe.

For Khorezm, it was the final nail in the coffin.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

|

This page was first published on 12 October 2008. It was last updated on 4 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2015. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |