|

Contents

Khorezm and the October Revolution

The Khorezm Soviet Republic

The Stalin Years

The Post-War Period

Depths of the Cold War

The Collapse of Communism

References

A poster of Karl Marx overlooks a Soviet parade in Lenin Square, No'kis, in the early 1980s.

Khorezm and the October Revolution

The task of outlining the history of Khorezm and the Karakalpaks during the relatively recent Soviet period is in someways harder than describing more

distant events. The published Soviet versions of events assert that, with the exception of a few religious or bourgeois reactionaries, the peoples of

Central Asia wholeheartedly welcomed the Revolution and gave it their full support. The accounts are so distorted and one-sided that they would be

laughable were it not for the chilling realization that either misguided loyalty or terror resulted in several generations of authors substituting

fantasy for reality. Sharaf Rashidov, the former Communist First Secretary of Uzbekistan, makes the point for us admirably in his book "Soviet

Uzbekistan", published shortly before his demise in 1983:

"The victory of the Revolution marked a turning point in the history of the peoples of our country. The cleansing wind passed over Turkestan as well,

sweeping away with it the dirt and the scum of the old world, a world of cruel social and national oppression, feudal and capitalistic exploitation,

the tyranny of the khans, rich landowners and tsarist officials, and lack of rights for the working people."

"A new epoch had come an epoch of intellectual renaissance, a rapid and steady rise of the economy and development of all national and ethnic cultures

of Central Asia, an epoch of friendship, brotherly co-operation, and mutual assistance of the peoples of our country."

Penned by one of Uzbekistan's most corrupt politicians, these words sum up the appalling hypocrisy of the former Soviet regime.

Sharaf Rashidov, First Party Secretary of the Uzbek SSR, 1959 to 1983.

Yet the alternative view was also biased, although not in such a ludicrous manner. Non-Soviet historians have argued that the response of the local

population varied from indifference to violent opposition and that their incorporation into the Soviet system was only achieved through Russia's

overwhelmingly superior military strength. What we lack in both accounts is any record of events from the point of view of the endemic population who

generally played a minor role in the events that shaped their lives for the next 70 years. Following independence, local people are now much more

willing to describe openly what life was like in Khorezm during the Soviet period and some local academics are researching the period from a new

standpoint. The danger now is that history is being rewritten, not always objectively, from the new nationalistic Uzbek, Turkmen, or Karakalpak

perspective. At the end of the day there is no substitution for an eyewitness account, but unfortunately only a handful have been published. Sadly

few of today's citizens can remember as far back as the events that followed the 1917 October Revolution but many remember the Stalin era, both before

and after the Great Patriotic War.

While the Russian Provisional Government attempted to continue the war against Germany throughout 1917, they were submerged by increasing lawlessness

at home. Finally, on 6 November, a group of Bolsheviks led by Trotsky stormed the Winter Palace and ousted the Provisional Government, opening the

way for Lenin to establish the All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

It was a time of major crisis. Russia had been devastated by the war. The Empire was disintegrating Poland, the Ukraine, Estonia, Finland, Moldova

and Latvia all declared independence, as did Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan following the humiliating peace treaty signed with Germany in 1918. Soon

Russia would be engulfed in the Civil War between the Red and White factions - for and against the Revolution.

Within Central Asia itself the main political response to events taking place in Russia was centred on the Russian community in Tashkent. At that time

the city consisted of two parts, the old Muslim town with a population of about 200,000 and the new and adjacent Russian quarter with a population of

about 50,000. Following the so-called revolution of February 1917, and the abdication of the Tsar, the official ruling Turkestan Committee effectively

vied for power with the unofficial Tashkent Soviet. As early as September, before the October Revolution, the Tashkent Soviet had proclaimed its

authority over the whole of Russian Turkestan and within days of the Revolution members of the Turkestan Committee had been arrested by local activists.

By the end of November the Tashkent Soviet had gained complete control of central Tashkent. Following the creation of a soviet government in Petrograd,

the soviets of Turkestan and Bukhara aligned themselves with Tashkent and a Council of People's Commissars of the Turkestan Region was formed, headed by

a prominent Bolshevik. Certain Tashkent Jadidists, including some future leaders such as the two Bukharans, Abdurauf Fitrat and the younger Faizulla

Khojayev, threw their hand in with the Bolsheviks, although many others wanted Muslim not Communist rule.

Amazingly neither the former Turkestan Committee nor the new Tashkent Soviet contained a single representative of the local Muslim population, essentially

excluding 95% of the population of Turkestan. Yet it was clear that many of the Jadidists, and others who could speak on behalf of the Muslim

majority, saw the Revolution as an opportunity to gain autonomy and self-governance, although not necessarily complete independence from Russia. An

All-Russian Muslim Congress that had convened in Moscow during 1917 had already proposed a democratic federal republic to govern the Muslim territories,

while a Muslim conference in Tashkent demanded Muslim autonomy for Turkestan within a Russian federal republic. In December an Extraordinary Muslim

Congress held in Khokand (the Khanate located in the Ferghana Valley) established an independent regional government led by young nationalists. It

declared its desire for a Pan-Turkic confederation of progressive Central Asian states, for the education and Westernization of its people, and for the

modernization of its religious establishments. At the very same time a vast and peaceful demonstration for autonomy took place in Tashkent.

Yet the Tashkent Soviet had held a Congress in November 1917 aimed at establishing the foundations of Soviet power in Turkestan, during which they

arrogantly resolved that Muslims should be excluded from all government posts! The Muslims appealed to Moscow to rein in the Tashkent Soviet, but

Stalin refused to intervene in this distant dispute. Locally the Tashkent Soviet clearly saw the Khokand government as a direct and highly popular

threat to its own existence and at a Congress of Soviets held in Tashkent in January 1918 it was declared "counter-revolutionary". Within a month

Red Army forces had surrounded and invaded the town, causing considerable loss of life and leaving only a handful of fugitive survivors to tell the

tale. By April 1918 the Bolsheviks in Tashkent had formed the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

The extinction of the Khokand government sent a brutally clear message to those Muslim leaders still contemplating national self-rule within Central

Asia. Resistance to Soviet rule now went underground in the form of a mujaheddin-like guerrilla movement, which the Bolsheviks derogatorily termed

the Basmachis, a term normally reserved for bandits and murderers. The first Basmachi campaign had taken place in Ferghana during 1918 and 1919 and

moved on to Tashkent in 1920. However the Basmachis were very poorly equipped and lacked co-ordination, even more so than the Red Army - itself a

rag-tag mixture of Russian army deserters and East European ex-PoWs. The arrival of Enver Pasha, the former Minister of War for the Ottoman Empire

during the First World War, at the end of 1921, provided the Basmachis with some dynamic leadership for a brief period, during which they managed to

take control of both Dushanbe and Bukhara. Enver Pasha soon built up a considerable following and succeeded in defeating the Red Army on several

occasions. He established links with the Basmachis in Ferghana and with the Yomut leader, Junaid Khan, who was fighting the Bolsheviks in the Qara

Qum, close to Khorezm. However this high profile campaign was short-lived and the Bolsheviks managed to ambush Enver Pasha in the Pamirs during 1922.

Even so the Basmachis continued their campaign in the region, continuing to embarrass the Soviets into the mid-1930s.

The successful suppression of the aspirations of the Muslim majority is all the more remarkable given the fact that Central Asia had been effectively

isolated from Moscow and Petrograd during the Civil War. The relatively small Turkestan Red Army had been forced to fight not just the Basmachis but

the more professional soldiers of the White Army, not just on one but on several fronts. As early as November 1917 officers from the former Imperial

army formed the first White opposition forces in south-eastern Russia, cutting communications between Tashkent and Moscow. By March 1918 the Civil

War had begun. Ural and Orenburg Cossacks took over control from local soviets and the moderately socialist Mensheviks formed an interim government

in the Volga city of Samara. By August the whole of south-east Russia was under the control of anti-Bolshevik forces, with General Dutov in control

of Orenburg. With the railway from Central Asia effectively blockaded and Moscow desperate for cotton supplies, they even had to revert to camel

caravans to ferry cotton from Khorezm to Emba. Because of the desperate lack of local fuel several railway engines were converted to burn fish that

had been dried in the port of Aralsk for the purpose. The smell must have been incredible! Meanwhile, in Transcaspia, the local soviet had been ousted

from power by anti-Bolshevik forces in Ashgabat, who then called on support from British forces in Persia. This cut the railway line to the Caspian.

The Turkestan Red Army was split, with some troops fighting Dutov on the Aktjubinsk Front north of Emba, some fighting to the east in Semirechye, the

largest force trying to contain the uprising in Ashgabat, and with a residual force left behind to maintain control in Tashkent. Even in the capital

the Bolsheviks were not secure a rebellion in January 1919 was violently suppressed, causing many deaths, which rang alarm bells in Moscow. In

retrospect it is remarkable that the Red Army eventually prevailed, a result that owes more to the lack of co-ordination between its opponents than

to its own prowess.

The behaviour of the Soviet regime after the Revolution was in sharp contrast to the promises that had been made before the Revolution. Lenin and other

leading Bolsheviks had frequently denounced Tsarist imperialism over the years and, once in power, Lenin promised racial equality and national

self-determination for Russia's many subject peoples. By July 1918 the Bolsheviks had already established the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist

Republic, or RSFSR, with its own constitution based on a free federation of independent nations. One of Lenin's other early decisions was to establish

a new Commissariat of Nationalities under the Chairmanship of Joseph Stalin, possibly an unfortunate choice. However like many other early promises

from the new regime, these ideals proved to be short-lived. Turkestan and the Steppe Region had become home to about 2 million Russian immigrants who

wanted to remain an integral part of Russia. The region had huge natural resources and the Bolsheviks had no desire to leave this vast region open to

British Imperialist interests. There was also increasing concern about the potential challenge that could emerge if the various Muslim territories of

Central Asia should unite to form a pan-Islamic State. By early 1919 the new regime had dropped any idea of independent nation states, let alone Muslim

states, in Central Asia.

From the first-hand account of Frederick Bailey, a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Indian Army who had been sent to Tashkent in charge of a small diplomatic

mission to make contact with the new Bolshevik rulers, the Russian city had become a dangerous and sinister place during the period of his residence

in 1918 and 1919. The city was under curfew and everyone was under suspicion, with the spies and agent provocateurs of the CheKa looking everywhere

for anti-Bolshevik sympathizers. Once found an enemy of the regime might be disposed of with no more than a pistol shot to the head or, if lucky, might

be sent to the forced labour camp at Perovsk. People's identity papers were checked constantly while the bourgeoisie were evicted from their homes and

stripped of their property and furniture by fanatical commissars. During the 1919 famine all of the trees across the city were cut down for fuel and

the Bolsheviks even stole food from the peasants, leading to a critical response from Lenin. In the centre of Tashkent the statue of General Kaufmann

had been something of an embarrassment during that year's May Day celebrations and in July it was removed from its granite pedestal to be replaced some

months later with a giant hammer and sickle.

It took time for these major events to have an impact on the backwater of Khorezm, which was way behind Khokand in terms of its political awareness.

There was no radical Russian enclave in Khiva to spread the Revolution, the merchants of Urgench being all anti-Bolshevik, along with the officers of

the local Russian garrison. Earlier that year Lenin had told the Seventh Party Conference that he did not want the peasants of Khiva to live under

the Khan's rule, but the Tashkent Soviet did not regard either the Khivan or Bukharan Khanates as a priority and for a while they remained independent.

Isfandiyar Khan, with the support of Colonel Zaitsev and Junaid Khan, made the most of the situation by hunting down local Jadidists and other radicals.

In November 1917 a number of Jadidists seem to have been put on trial (the evidence is not clear) but were saved from execution. Despite the fact that

the internal situation within the Khanate remained unstable with the Turkmen raids continuing unabated, discipline within the Russian garrison had

fallen to such a low level that Zaitsev ordered the pro-Bolshevik infantry regiments back to Petro-Aleksandrovsk. Zaitsev had originally intended to

spend the winter in Khiva and to then join up with Dutov's forces in Orenburg, but his Cossack forces were growing increasingly restless and he decided

to change his plans. In January 1918 he left Khiva for Charjou, where he gained reinforcements in readiness to attack Tashkent while its forces were

engaged in overcoming the uprising in Khokand. But when he encountered Soviet troops just outside of Samarkand, Bolshevik supporters persuaded his

Cossacks to lay down their weapons, forcing Zaitsev to flee as a fugitive. After reaching Ashgabat he was quickly spotted and arrested.

The departure of the Russians left Isfandiyar Khan's regime totally reliant on Junaid Khan, who commanded the only pro-Khivan armed forces in the

Khanate. Junaid Khan now acted through the timid Isfandiyar to increase his grip on power. The Majlis was abolished and in May the Jadidist

leaders who had earlier been put on trail were executed. The handful of remaining Jadidists, who had since gone underground, escaped to Tashkent to

form a small revolutionary committee in exile, known as the Young Khivans.

Junaid Khan was selfishly ambitious, opposed to the Bolsheviks and reformers not on idealistic grounds, but because they threatened his control over

Khorezm. While Isfandiyar was left as the titular head of state, Junaid Khan began to install his own system of control, just like the inaqs

of old. He set up a network of military commanders to rule the separate regions of Khorezm, using the services of the established court officials but

reporting directly to him. He began the construction of a palace at his village of Bedirkent, close to Takhta, which effectively became the new

capital of Khorezm. Taxes were raised, especially for the Uzbeks, who were also forced to undertake compulsory labour service to clean the irrigation

canals. All Turkmen were ordered to arm themselves at their own expense and to make themselves available for military service. Junaid faced a limited

rebellion from his old rival Yomut leaders, but these were soon overcome and by late summer he was firmly in control of the local Yomut population.

At the end of September he raided Urgench and stole money and property from the local Russian merchants and banks, arresting some Russians in the

process. However the Russian garrison at Petro-Aleksandrovsk had just been reinforced with Red Army soldiers under the command of a new Bolshevik

military commissar, Nikolay Shaydakov, who ordered Junaid Khan to release his Russian captives. Junaid Khan complied but warned Shaydakov not to

interfere in Khivan affairs, realizing that he was still vulnerable to Russian intervention, especially if Isfandiyar appealed to Petro-Aleksandrovsk

for help. Junaid decided that his security would be enhanced with Isfandiyar out of the way, especially as he could then rule through Isfandiyar's

more malleable and grateful brother, Sayyid Abdullah. He instructed his eldest son to go to Khiva and assassinate the Khan.

A month or so earlier Junaid had refused a request from Ashgabat to slow down the Soviet advance on Transcaspia by attacking the garrison at

Petro-Aleksandrovsk he felt that the mission was too dangerous, especially since Russian reinforcements could be quickly despatched by steamer from

Charjou. At the same time he knew that the nearby garrison posed a constant threat to his position. As autumn turned to winter navigation on the

Amu Darya became impossible and Junaid Khan made his move. Turkmen forces crossed the Amu Darya at six separate locations and laid siege to

Petro-Aleksandrovsk. But, quite unexpectedly, a steamer from Charjou managed to get through with reinforcements and the siege was broken after only

eleven days. In the following spring Russian troops returned from Charjou and defeated Turkmen forces on the left-bank in the region of Pitnyak.

The Petro-Aleksandrovsk Soviet was keen to annex Khiva, but Tashkent needed all the troops it could find for the Transcaspian front. Instead they sent

a peace mission to Khorezm and negotiated a settlement with Junaid Khan, known as the Treaty of Takhta, which was signed on 9 April 1919. Khiva

would remain independent and would re-establish normal diplomatic relations and trade with Russia, who in turn would offer an amnesty to all Turkmen

charged with anti-Soviet activity. However relations with Russia remained difficult with Junaid reacting uncooperatively to a request to supply troops

for the Transcaspian campaign and then refusing to accept the Russian diplomatic representative sent to Khorezm in accordance with the terms of the

Treaty. That summer also saw a revolt by a detachment of Cossacks based at Shımbay, who allied themselves with local Karakalpaks to take control

of the entire delta region, from No'kis up to the Aral coastline. When Shaydakov and his troops steamed down the Amu Darya to No'kis to put down the

revolt they were annoyed to be fired upon by Junaid's Turkmen supporters. After relieving No'kis Shaydakov headed back to Petro-Aleksandrovsk in fear

of another Turkmen attack following the onset of winter. In fact Junaid Khan was already discussing the possibility of such an attack with the rebels

in Shımbay.

However, for the Soviets, the tide was turning. By October the European Red Army had defeated Dutov and Soviet forces from Tashkent had reached Qizil

Arvat in Transcaspia. Moscow had only just established a new government for Turkestan, the Commission for the Affairs of Turkestan, and the focus now

began to turn on the still independent territories of Bukhara and Khiva. For once the smaller province of Khiva was singled out as the priority, given

its outright hostility to Russia and its ongoing instability, another revolt by Junaid's Yomut rivals having only just broken out again in Xojeli and

Kunya Urgench. At the same time the constant flow of disaffected radicals from Khiva had swollen the ranks of the Young Khivans in Tashkent from just

over a dozen to a militia of around five hundred. In November the Turkestan military authorities sent Skalov, their new military representative for

Khiva, to Petro-Aleksandrovsk to organize an invasion, just as a relief force from Charjou was extricating Shaydakov's forces from No'kis where they

had been under attack by a combined force of Turkmen and rebel Cossacks.

Skalov crossed the Amu Darya on 25 December with 430 soldiers, including some leading zealots like Faizullah Khojaev. They took Khanqa and Urgench

without a struggle, only to find themselves besieged in Urgench by Junaid Khan's troops for the following three weeks. Meanwhile Shaydakov's army of

400 soldiers defeated the Cossack and Karakalpak rebels at Shımbay before crossing the river to take control of Xojeli, where their numbers were

swollen by rebel Turkmen forces opposed to Junaid Khan. After the fall of Kunya Urgench Junaid Khan retreated to Bedirkent to face Shaydakov's army

from the north and Skalov's army to the south. After a two-day battle at Takhta Junaid Khan escaped into the Qara Qum. Khiva was taken on 1 February.

With the Red Army in control Sayyid Abdullah Khan, the very last Qongrat Khan and member of the Chinggisid dynasty was forced to abdicate with his power

transferred to a temporary revolutionary committee led by Hajji Pahlavan Yusupov. Only a tiny minority of the Young Khivans was Communist, yet Tashkent

immediately responded to this factions request for the establishment of a soviet republic in Khorezm. A political delegation was quickly despatched

to conduct elections to a nationwide congress of soviets. On 27 April the First All-Khorezm Congress of Soviets met and agreed to abolish the

Khanate in favour of an independent Khorezm People's Soviet Republic. The Young Khivans were now in control of Khorezm, heading 10 of the 15 available

departments, and with the chairman of their central committee, Hajji Pahlavan Yusupov, acting as premier.

Later that year the Khorezm People's Soviet Republic concluded an extraordinary formal treaty with the RSFSR, which superseded all previous agreements

and withdrew all former Russian claims and rights over the territory. Russia recognized Khorezm's full independence, but offered a voluntary economic

and military union and assistance with economic and cultural development, including a campaign against illiteracy and educational resources. All

property, land concessions, and rights of usage of the Russian government, Russian citizens, or Russian companies were transferred to the new government

of Khorezm without compensation. Even the assets of the Amu Darya Flotilla were transferred to a joint Khorezmian and Bukharan river authority. Soon

teachers, doctors, and military instructors arrived from Tashkent and elsewhere with supplies and equipment. Work began to establish 35 new schools

and 15 adult colleges, as well as Khorezm's first national university. Canals were repaired, bridges were built and the telegraph was extended. It

was all too good to be true.

The Khorezm Soviet Republic

As we have just mentioned, in September 1919 a new Turkestan Commission was established in Tashkent tasked by Lenin to rally the previously

alienated Muslim masses to the Soviet cause. It was led by Shalva Eliava, a Georgian with little knowledge of Central Asia and soon ran into problems

with the local Turkestan Communist Party, which now had a Muslim majority. The Muslim communists were keen for Turkestan to gain more autonomy as a

Soviet Republic of Turkic Peoples, with its own Turkic Red Army.

These ideas were anathema to General Mikhail Frunze, who arrived in Tashkent the following February, effectively taking control of both the Turkestan

Commission and the Turkestan government. As commander of the Red Fourth Army as well as the Turkestan Red Army, Frunze had only just gained control

of Siberia after having earlier defeated Dutov's forces in the Urals. He was now determined to restore order in Turkestan, revive its economy and draft

a new constitution that would be acceptable to Moscow. Frunze needed support from the native Muslim majority and quickly dismissed some of the

anti-Muslim government leaders, courting popularity by distributing food and seed to the ordinary people. Frunze rejected the idea of a Turkic republic,

seeing the petty bourgeois views of the Muslim leaders as unrepresentative of the Islamic majority. Rather than unite the separate Oblasts

of Turkestan, along with the Amu Darya Military Division and the former Khanates of Khiva and Bukhara, Frunze believed it should be divided along

ethnic lines, between the Uzbeks, Turkmen, and Kyrgyz. He told Lenin that the main obstacle was a shortage of reliable native leaders.

General Frunze only remained in Tashkent until September 1920, when he was ordered back to the Russian southern front. During his short stay the

Turkestan Army had regained control of Transcaspia and had overthrown the Khanate of Bukhara, installing Faizullah Khojaev as the President of a new

Bukharan Soviet People's Republic. Within months Frunze had cornered General Wrangel's army in the Crimea, forcing it to evacuate to Constantinople.

With the end of the Civil War in sight, Khorezm was still polarized by the enmity between the settled Uzbek and the nomadic Turkmen populations. The

Young Khivans who dominated the government in Khiva were all Uzbeks and they wanted to see the supporters of Junaid Khan, who had seized control of

the Khanate, punished. About one hundred Turkmen were arrested and shot and others were disarmed, while punitive raids were directed against villages

suspected of supporting the Turkmen rebels. The Turkestan Commission were concerned about unfolding events and sent a team of investigators to Khiva,

led by Valentin Safonov, a former Bolshevik army commander. He was alarmed to find that the Young Khivan government had no liking for Marxist socialism

whatsoever and was doing its best to block its introduction. It had even gained control of the nascent Khorezmian Communist Party.

Safonov convened an all-Turkmen Congress in the small left-bank Khorezmian town of Porsa, securing the support of the Turkmen leaders to overturn the

Young Khivan government. A mass demonstration was engineered in Khiva against the government in March 1921, providing an excuse for the Red Army to

capture the government offices and to oust the Young Khivans. A governing provisional revolutionary committee was formed, consisting of two Uzbeks,

one Turkmen, one Qazaq and a member of the Komsomol. Elections were held to form a Second All-Khorezm Congress of Soviets, which met in May to form

a new government, devoid of Young Khivans. Many of the latter had fled into the Qara Qum to join Junaid Khan, whose following increased dramatically

after Safonov's intervention into Khorezmian affairs.

The Russians kept a close eye on subsequent events, purging the supposedly independent government and the local Communist Party at will. In October

several members of the former government were executed or imprisoned for counter-revolutionary activities, while others were arrested during the

year-long purge that followed.

By now Lenin and the Central Committee were fully in control and it was time to establish an administrative structure and constitution for the new

Bolshevik State. Although Marx had argued that nation states would disappear as workers united across international boundaries, the government of such

a huge ethnically and linguistically diverse territory was unthinkable without strong provincial subdivisions. Lenin had promised "self-determination

for the toilers" and he intended to deliver this through his new nationalities policy, by transforming the RSFSR into a federation of national states

that would no longer be independent but would be "partially autonomous". Yet before this policy could be implemented the federation was already being

enlarged by the addition of new Bolshevik republics. The ratification of the Union Treaty on 30 December 1922 joined the RSFSR to the Ukraine,

Belarus and the Transcaucasus to form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR.

Lenin had already written to the Communist Party in Tashkent in 1920, asking them to investigate how many national republics should be established in

Turkestan and how they should be named. The task of ethnically dividing up Turkestan was something like the equivalent of trying to divide up a

multi-ethnic country like Afghanistan today. The idea of ethnically defined nations with fixed borders was quite alien to the essentially tribal

people who lived there, whose concept of identity was based on family and clan ties and whose concept of territory was linked to their farm settlement

or grazing lands. When the Bolsheviks sought advice from the renowned Orientalist Vasiliy Barthold he told them that the idea ran contrary to

historical experience and would be a great folly. However the politicians were motivated by the need to divide and rule and to eliminate any

justification for separatism or Turkic or Islamic unification. Some foresighted Islamic leaders were dangerously proposing that European Marxism was

unsuited to the tenants of the Muslim world and would simply encourage Russian chauvinism. Using information from Russian ethnographers,

apparatchiks in Moscow divided the RSFSR into artificial "nations", ensuring that none of them could dominate its own region alone, save for

Russia itself. Each was required to have an external foreign border, to emphasize that they were nations and not just states. In Central Asia this

resulted in the creation of six artificial nations based around six former tribal confederations: the Qazaq, Kyrgyz, Karakalpak, Turkmen, Uzbek, and Tajik.

The opinions of the local people counted for little in this decision. Khiva fought hard to maintain the integrity of the ancient land of Khorezm for

a number of years, but was constantly overruled by Moscow.

The Soviet Government remained concerned that both Khorezm and Bukhara remained hotbeds of counter-revolution, under the control of the bourgeoisie

rather than the proletariat, despite the expulsion of the Young Khivans. Stalin wanted them transformed into "fully socialist" societies, so it was

decided in 1922 that the whole of Turkestan, including Khorezm and Bukhara, should operate as a single economic unit. The Central Asiatic Economic

Council was formed to integrate all of the region's agriculture, irrigation, post and telegraph systems, trade and monetary systems. Meanwhile

Moscow took back control of the Amu Darya Flotilla. Finally the Communist parties of Khorezm and Bukhara were to be merged with that of Russia.

The Russian Central Committee sent a senior hard-line Bolshevik to Khiva to conduct a ruthless purge of both the party and the government. The

membership of the Khorezmian Communist Party was reduced from a few thousand to a few hundred, with the expulsion of all merchants, tradesmen and

landowners. Following the purge, in October 1923, the constitution of Khorezm was changed to disenfranchise "all non-toiling elements". Restyled as

the Khorezmian Soviet Socialist Republic, Khorezm had finally qualified as a "socialist" republic and now formally requested membership of the USSR.

Within three years it had been transformed from an independent ally to a docile puppet of the Russian regime.

Junaid Khan kept up his violent opposition through the winter of 1923. In December the new Khorezmian government faced a major revolt in response

to increased taxes and the introduction of secular schools. Junaid Khan, supported by ten thousand or more Uzbek and Turkmen rebels, laid siege to

Khiva for nearly a month, recapturing it with the help of local clerics and merchants for a short period in January 1924. Tashkent ordered in a

3,000-strong Red Army camel cavalry detachment, supported by nine aircraft, and the demonstration was suppressed. Following instructions from Moscow,

the government reduced taxes and permitted the medressehs and maktabs (where children studied religious texts) to reopen. Junaid Khan agreed

to a treaty, which he maintained until some of his partisans were executed. As a result of that action he resumed his opposition until a general state

of mobilization was declared against him. Following a six-week campaign in the Qara Qum, Junaid Khan's resistance was broken. He finally fled to

Persia in 1928.

It is a pity that we do not have a trustworthy account of life in Khorezm at this very unusual time - after 1917, entry into the two Khanates of Khiva

and Bukhara became almost impossible for European travellers. The foolhardy Austrian carpet dealer, Gustav Krist, who had formerly been a PoW in

Central Asia, did manage to get close, thanks to a chance meeting with some Yomut tribesmen on a Caspian beach in northern Iran in 1923. The Yomut

smuggled him into Turkmenia, where he borrowed the identity and papers of an old Austrian friend living in Qizil Arvat, who was a naturalized ex-prisoner

of war. Krist travelled across the desert from Merv to Eldzhik (Iljik) on the Amu Darya just to the south of Khorezm, escorted by a troop of Desert

Police on camelback, then took the steamer 70 km upstream to Charjou. Even at this early date Charjou had already become a large cotton-growing

centre, huge stretches of land having recently been planted with cotton instead of corn. At the time of his visit the town was busy with the cotton

harvest, with many caravans and boats bringing in raw cotton from the surrounding villages to be processed at some of the new cotton-ginning mills that

had recently been built in the town. The local people were still practising their Muslim religion as normal, but now the red flag flew above every

government building, red pennants flew from every shop door and pictures of Lenin adorned the chai khanas. The former Beg had been driven out

of his citadel in 1920, which had already been turned into a museum. When Krist reached Bukhara he found that it was still a thriving commercial and

religious town, with 21,000 future mullahs still receiving Qur'anic instruction in its medressehs. However there were strange juxtapositions, with

Soviet slogans and portraits hung up beside shelves of Islamic texts, and with even the Imam at the Mir Arab Medresseh having a poster in his cell

proclaiming "Proletarians of all Lands Unite!" One disturbing observation was that the mosaics around the lower reachable parts of many of the

monumental buildings had been removed, having been previously sold to dealers and collectors.

Lenin died in January 1924, missing the endorsement of the new Constitution of the USSR by ten days. Local Communist parties, including those of

Turkestan, Khorezm and Bukhara, approved the proposed national delimitation of the USSR and that following autumn their respective governments gave

formal assent to the measure. Each new "nation state" was to become a Soviet Socialist Republic, or SSR, with its own constitution, its own legislative,

executive, and judicial institutions, and its own party structure. Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics, or ASSRs, would have some degree of autonomy

but would be subordinate to an SSR. Each SSR would be divided into provinces or Oblasts. Each would be named after its largest ethnic

population. All would be members of the USSR.

Within Central Asia, the former Khanates of Khiva and Bukhara were the main losers in the process, probably deliberately so, their territories being

divided up between the new national entities. Khorezm was split into three separate parts. The left bank region of Dashoguz and Kunya Urgench went

to the Turkmen SSR (including a large community of Uzbeks), while the whole delta region and much of the right bank was designated the Karakalpak

Autonomous Oblast within the Kyrgyz ASSR of the RSFSR, with its capital at To'rtku'l. This was a positive development for the Karakalpaks,

who finally gained a homeland, despite the fact that they made up less than 40% of its population. The Kyrgyz ASSR also included the Kara-Kyrgyz

Autonomous Oblast. The remaining part of Khorezm was essentially the heart of the old Khiva Khanate and included Khiva, Urgench and Hazarasp.

It was renamed the Khorezm Oblast and was incorporated into the Uzbek SSR, which also happened to include the Tajik ASSR. The Uzbek SSR

essentially consisted of most of the former three Khanates of Khiva, Bukhara and Khokand. It is likely that the constant conflict between the Uzbek

and Turkmen populations of Khorezm contributed significantly to the Russian decision to partition the country.

Over time these various Central Asian entities have been renamed and regrouped, although the basic system remained in place until the dissolution of

the USSR. The Kyrgyz ASSR was renamed the Kazakh ASSR in 1925. The Tajik ASSR became an SSR in 1929, splitting away from the Uzbek SSR; the Kyrgyz

Autonomous Oblast became an ASSR in 1926; the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast became an ASSR in 1932 and was transferred from the Kazakh

ASSR to the Russian SSR; and both the Kazakh ASSR and the Kyrgyz ASSR became SSRs in 1936. Following persistent lobbying from Tashkent, Moscow decided

to transfer the Karakalpak ASSR to the Uzbek SSR in 1936. This was a popular move for the Uzbek population of the province but a retrograde one for

the Karakalpaks who have much more in common ethnically with the Qazaqs.

In practice the political boundaries of Central Asia had been totally redrawn. The old tribal territories and their rulers had become obsolete,

creating the opportunity for a new political elite to emerge. Those in the vanguard of the local Soviet movement soon learnt that acquiring a position

of status in this new political environment offered unprecedented political and economic rewards. The new Uzbek SSR rapidly came under the domination

of activists from the Tashkent, Ferghana and, to a lesser extent, Samarkand regions. Thus the First Party Secretary, Akmal Ikram, came from the

Tashkent Oblast, and all of the First Party Secretaries up to 1959 came from either Tashkent or Ferghana. From the very beginning politicians

from Khorezm (and Bukhara) were viewed with suspicion in Tashkent, while the Surkhandarya and Kashkadarya Oblasts were regarded as too

backward to exert any national influence.

As early as 1920 Lenin had approved a plan to regenerate cotton cultivation in Central Asia, primarily to support the Russian textile industry.

However the political events of 1920 to 1922 led to massive economic disruption in both Khorezm and Bukhara, with cotton exports to Russia falling

to just 5% of their pre-First World War level. Agriculture did recover, although even by 1924 exports from Khorezm had only reached 30% of

their 1913 level. During the early 1920s cooperatives were set up to repair and expand the irrigation network and attempts were made to reform

land ownership and water rights. Some land was confiscated from rich beys. Not surprisingly Tashkent and Ferghana were deemed to be the

most suitable locations for new manufacturing industries.

The onset of Lenin's illness had meant that three old-time Bolsheviks, Zinoviev, Kamenov and Stalin became the de facto ruling triumvirate of the USSR,

effectively in control of the Politburo. After Lenin's death divisions opened up between the ruthless and ambitious Stalin and his two unsuspecting

colleagues. Stalin had already outmanoeuvred the once powerful Trotsky, and now groomed new supporters on the Politburo. Secure in his position,

Stalin now demoted Kamenov for publicly attacking his economic policy and in the following year dismissed Zinoviev over a scandal involving the

organization of a Red Army opposition group. One year later both Zinoviev and Trotsky were expelled from the Party and the way was open for Stalin

to purge his opponents en masse.

|

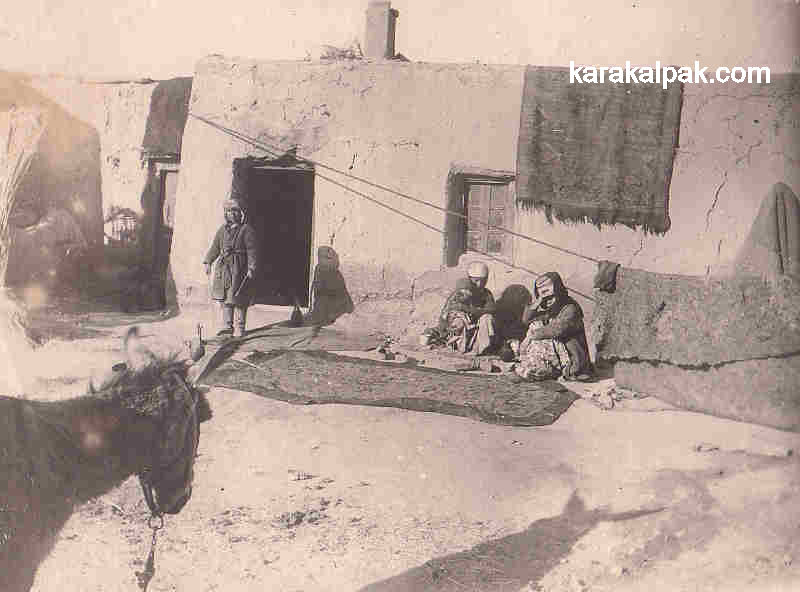

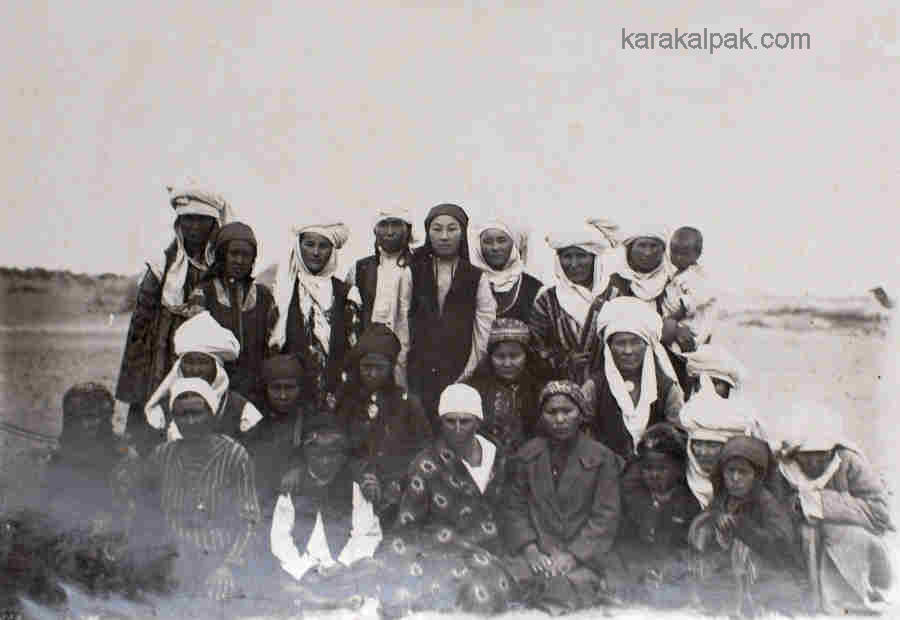

Karakalpak women and children photographed by Aleksandr Melkov in 1928-29.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

At the XV Party Congress, in December 1927, Stalin announced that the fundamental objective was to change the agricultural economy by amalgamating small

peasant farms into large-scale enterprises and to open new factories and expand the industrial base. Only weeks later a crisis developed over a major

shortfall in the government's domestic purchases of grain, threatening a famine among the urban population. Stalin blamed the kulaks, the

land-owning farmers and peasants, for withholding grain and disrupting Soviet economic policy. "Emergency measures" were ordered by the Politburo,

involving the raiding of peasant farms, illegal searches and the requisitioning of hidden grain stocks. In July 1928 Stalin called on the party to

"strike hard at the kulaks".

In fact 1928 became a crucial year. Stalin was unsettled by the spectre of chronic famine and was also concerned about the stagnation of industrial

production. His biographer described him at this time as living in a half-real, half-dream world of statistics and indices in which no target and no

objective seemed to be beyond his or the party's grasp. His favourite saying was that "there are no fortresses that cannot be conquered by the

Bolsheviks".

The outcome was the first Five Year Plan. It ambitiously set a target of a 250% increase in industrial output and a 150% increase in

agricultural production. But it was far more than an economic plan it was to be the first real implementation of Marxist ideology, with the

abolition of the private sector and the elimination of the exploitative class. Agriculture would be collectivized throughout the USSR. The farmlands

and property of the hated kulaks would be expropriated and held collectively, eliminating the hard core of anti-Soviet resistance in the

settled agricultural areas. In the steppes, deserts and mountains of Central Asia it would break the resistance of the nomads - the Turkmen, Kyrgyz,

and especially the Qazaqs, who wanted nothing more than the expulsion of the Russian settlers from their lands. The strong culture of these pastoral

people made them impervious to Soviet indoctrination; they were mobile and uncontrollable and had no desire for promised Soviet improvements such as

schools. The Soviets realized that they could only overcome this resistance through the compulsory "stabilization" of the nomadic populations of

Central Asia. This would involve the expropriation of the lands and herds of the rich beys, and the forced settlement of the nomads on

collective and state farms.

In December 1929 celebrations were held to mark Stalin's 50th birthday. The slogan of the day was prophetic: "Stalin is the Lenin of today!" Now only

one man was in charge of Soviet affairs.

The Stalin Years

The First Five Year Plan was adopted in April 1929 at the XVI Party Conference. The objective was nothing less than to change the minds and values of

the entire nation, by eliminating private property and destroying traditional ways of living and working. It aimed to make every worker, peasant and

nomad an employee of a state-controlled enterprise. Once the peasant had lost his attachment to his land and the nomad his attachment to his livestock,

they would at last realize that their true interests lay in the advancement of their collective and the advancement of the state. It was dubbed the

"Second Revolution". It was the beginning of Soviet totalitarianism, where state control would be exercised forcibly over every aspect of economic,

social and cultural life.

|

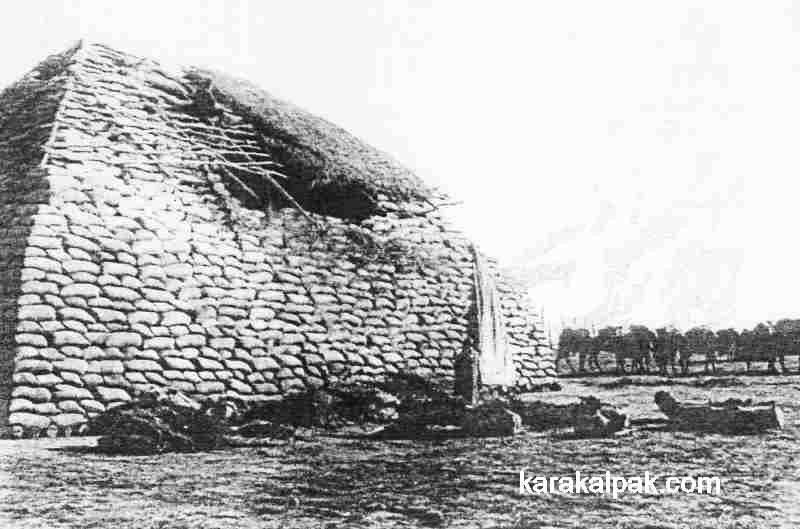

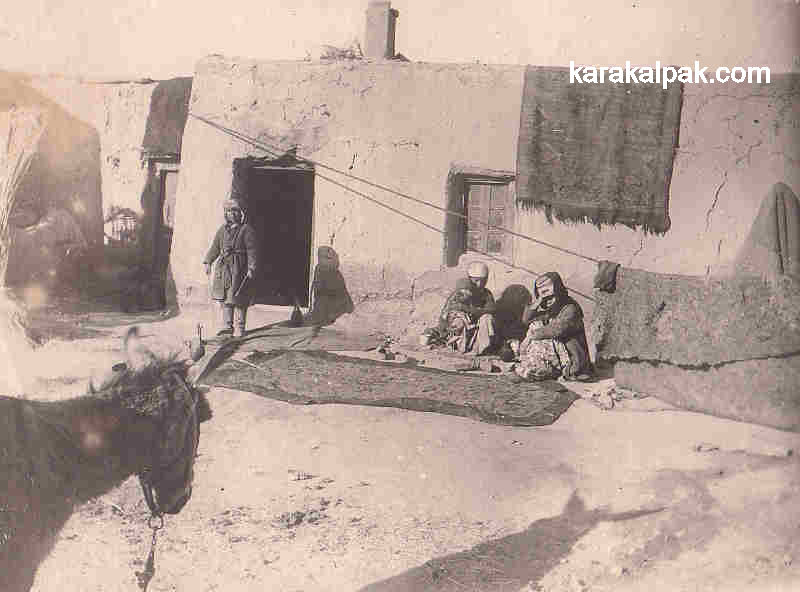

Awıl of Mu'yten Karakalpaks at Qazaqdarya, photographed by Melkov in 1929.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

Mu'ytens waiting by river ferry boats at Qazaqdarya. Photographed by Melkov in 1929.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

It turned out to be an unmitigated disaster for the Soviet Union as a whole. The rural economy descended into pandemonium. In many villages farm

collectivization was resisted passionately. Families slaughtered their cattle, smashed their implements and burned their crops. In some cases villages

were surrounded by GPU secret police units and relocated at gunpoint. Whole communities were uprooted and moved. The so-called kulaks were

deprived of their property and then barred from joining the new collectives. Some kulaks were sent to concentration camps in the Aral

region the GPU secret police opened one camp at the old military prison on Vozrozhdeniye Island in the middle of the Aral Sea and one or more at Aralsk.

Other kulaks were deported to remote regions of Siberia or were resettled on low-quality land, and some were even murdered. Often the

implementation of these directives was left to untrained and uneducated officials and party underlings, who often misunderstood the purpose or process

of collectivization and acted in a crude and heavy-handed way. The process was also open to considerable abuse and corruption and was an excuse for

local people to settle old scores, or to attack peasants who were resistant to the cause or just owned a few cows and chickens.

Peasants who resorted to violence or resisted collectivization were treated as criminals and were herded into labour camps, and were subsequently

employed as "forced labourers" on building canals and railways. Even obedient workers were not immune from coercion. Stalin had introduced a new

labour policy in 1929 under which workers could be directed to work in specific factories or collective farms.

The greatest resistance to collectivization occurred among the true pastoral nomads, particularly the Qazaqs and the Turkmen. When the policy was

announced, many livestock-breeders simply killed their herds rather than hand them over. Others simply packed up and migrated out of the country.

There were many violent local uprisings and many Party activists were killed. The results were staggering. In the Qazaq ASSR the number of cattle

fell from 7.4 million in 1929 to 1.6 million in 1933, while the number of sheep fell from 21.9 to 1.7 million over the same period; by 1935 only

63,000 camels remained out of over 1 million. By 1941 only 885,000 horses remained from an original population of 3.5 million.

The resulting cataclysmic collapse in agriculture gave rise to the 1931-33 Soviet famine. Statistics show that out of a population of 6.2 million

in 1920, some 1 million Qazaq people died during the collectivization and subsequent famine. However some Qazaq scholars believe the number could

have been as high as 2 or even 3 million! In addition possibly one million people migrated into China, Mongolia, Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey, although

some returned later. Statistics show that the number of Qazaq households fell from 1,233,000 in 1929 to 565,000 in 1936. The death toll in the Ukraine

was even higher. Even Stalin himself admitted privately to Churchill that over 10 million kulaks had probably disappeared as a result of

collectivization!

Not surprisingly within Khorezm the greatest resistance to collectivization came from the nomadic Turkmen population. Sadly the full story of the

uprisings across the Turkmen SSR has never been told, having been completely suppressed by the Soviets and ignored in the West. Perhaps we will never

know the details. There seem to have been several bloody revolts against collectivization in the 1930 to 1931 period, a mass culling of livestock and

an upsurge in the local Basmachi campaign. The late 1920s had also seen the development of a subversive movement, known as Turkmen Azatlygi, or

Turkmen Liberty, which was anti-Soviet and anti-collectivization, and gained considerable local support, both from the "toiling population" and from

intellectuals and senior politicians. Stalin responded to these events in the usual way, with iron-fisted repression and a subsequent purge. During

the 1930s almost an entire generation of intellectuals was liquidated in the Great Terror, including most of the senior Communist leadership, as we

shall shortly see.

On the other hand in northern Khorezm the implementation of collectivization seems to have progressed quite smoothly. Most of the Karakalpaks in

the delta lived within extended families that were essentially already operating as a collective unit, and the collectivization process involved little

more than combining several family groups into a single economic unit. Furthermore many ordinary peasants were glad to be rid of their former greedy

and oppressive landlords. An uprising in Taxta Ko'pir in 1929 has been previously misinterpreted as an indicator of local resistance, but recent

research has suggested that this was little more than a domestic disturbance sparked by a feud over a woman. This parallels the findings of the

American researchers, Kamp and Zanca, who have recently been interviewing old people in Namangan and Nurata. In hindsight many respondents supported

collectivization because of the material improvements that followed in their daily lives, and because of the introduction of universal schooling for

boys and girls that occurred at about the same time. Of course these supporters were the survivors looking back on events retrospectively; the

kulaks who were killed or exiled might well have told a different story!

|

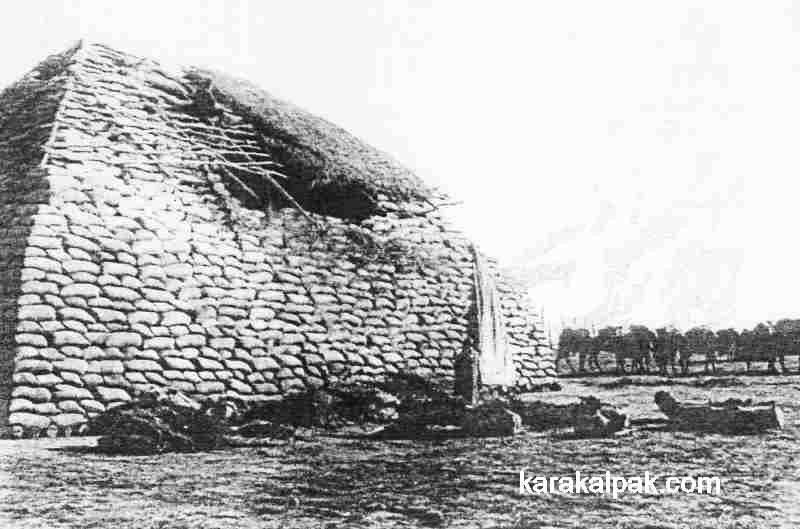

A street close to the bazaar in To'rtku'l, winter of 1934.

Image courtesy of the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

New collective enterprises were established progressively throughout Khorezm during the 1930s. Two types of farm appeared: the state farm, or

sovxoz (an abbreviation of sovetskoe khoziaistvo) and the collective farm, or kolxoz (an abbreviation

of kollektivnoe khoziaistvo). The former was the full property of the Soviet government, whose manager operated it with hired labour; while

the latter was supposed to be a self-governing co-operative made up of peasants who voluntarily pooled their means of production. There was also

the toz, a society for joint land cultivation, where the peasants kept title to their own plot of land, livestock and equipment and

the artel, where each peasant retained his own livestock and a private garden plot. The fishermen at Moynaq and Aralsk were also

organized into kolxoz.

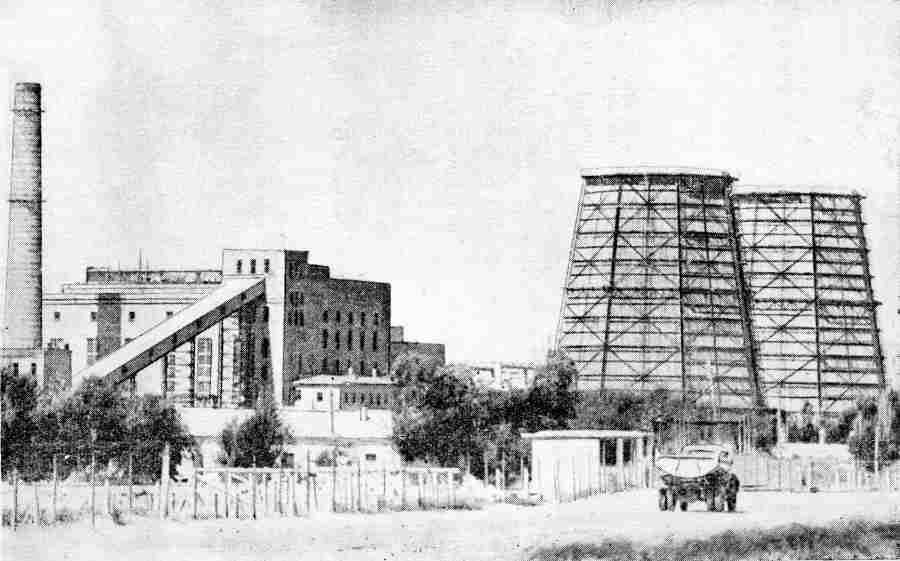

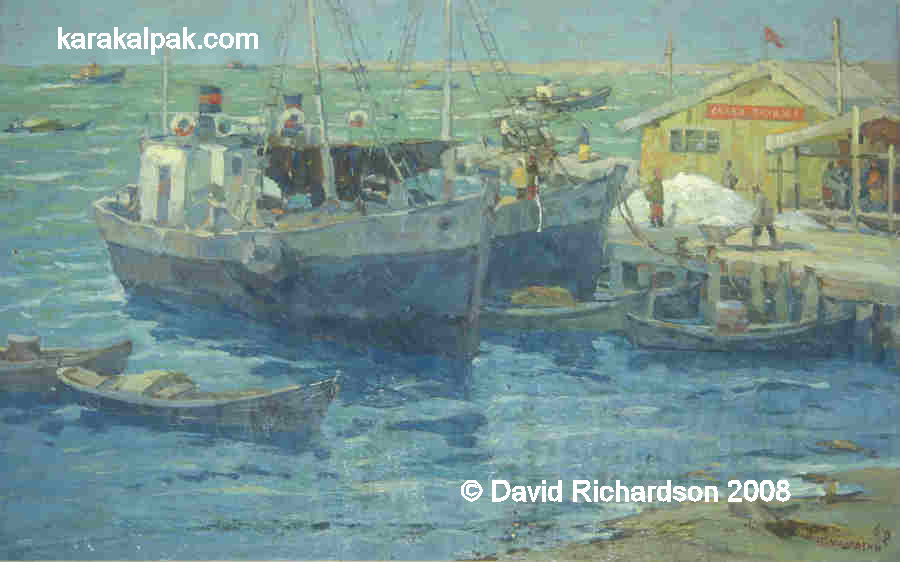

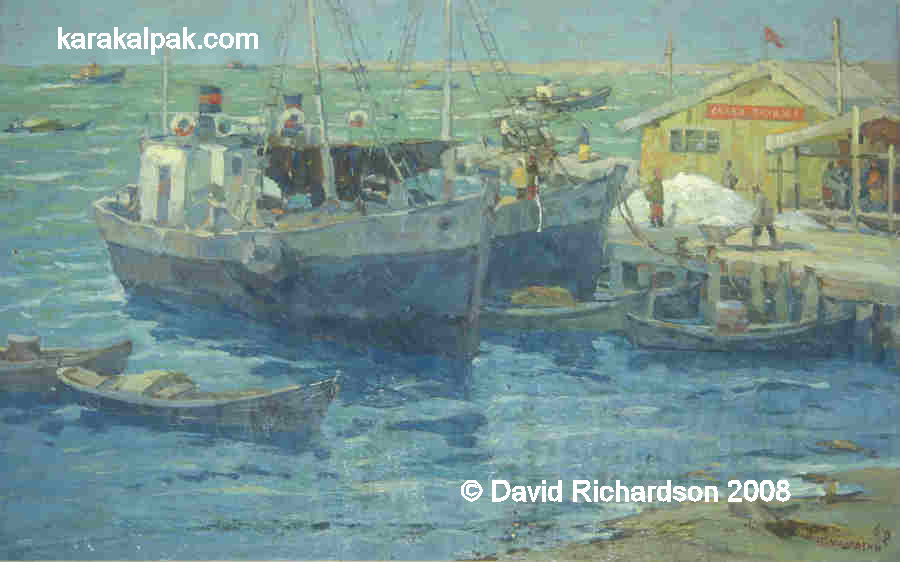

Qayıqs at the port of Moynaq, probably photographed in the 1930s.

Image courtesy of the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

The original intention was that the sovxoz would be the model to which all farm collectives should aspire. In reality the enormous

resistance to full collectivization forced the authorities to accept the artel as the most common, indeed almost the universal type of

collective. By 1933 about 96% of Soviet farms were essentially of the artel type, acting principally under the umbrella of

kolxoz rather than sovxoz. This somewhat defeated the original purpose of the whole collectivization exercise.

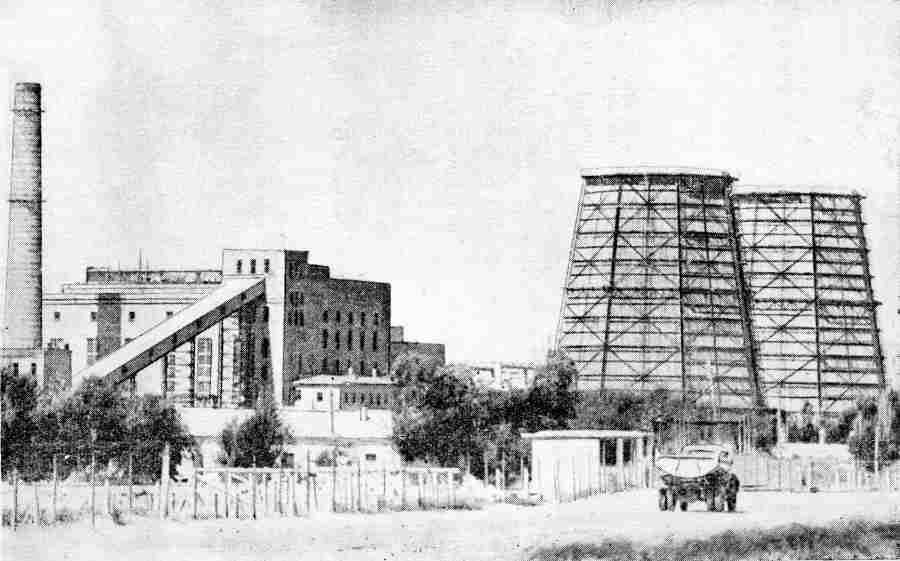

Leading workers from the sovxoz named after Lenin, Xojeli region, 1930s.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

Even so production targets were still rigidly enforced and Stalin even introduced military tactics to encourage their achievement, known as the

"shock quarter" the final quarter of the calendar year, when an all-out effort to boost output was organized. In September 1933 there was a

conference in Karakalpakia to rally the shock-workers on the collective farms. The insistence on target achievement coupled with the elimination of

private ownership led to illogical behaviour, such as sheep being sheared to maximize wool quotas at the onset of winter in the knowledge that the

animals would be unable to survive the winter.

Zbay Doshanova, a cotton-picker from the kolxoz named after Telman, Shımbay region.

Classed as a great toiler or Stakhanovka, she used to pick up to 120kg of cotton per day. Image courtesy of the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

Khorezm had been selected as one of the priority regions for expanding cotton production from as early as 1929 because its soil and climate were seen

as being ideal for growing cotton. One aspect of the 1929 Plan was to achieve "cotton independence" or cotton self-sufficiency. The argument was that

it made sense to encourage the Central Asian collectives to switch from grain, which could be grown anywhere in Russia, Ukraine, or Siberia, to cotton,

which could not be grown elsewhere in the Soviet Union . This led to enormous pressure being applied to the new collectives to plant cotton, pressure

that they resisted because the price for cotton was low. At first political commissars were assigned to the collectives to ensure compliance but then,

in 1934, cotton prices were raised by 500%. Cotton immediately became highly attractive, being referred to as "white gold" and the cotton acreage

soon increased. But there was still a problem: the crop yields remained dismally low. This was partly because canals had been built without proper

allowance for subsequent drainage, coupled with poor irrigation practice, which resulted in the land becoming salinized the age-old curse of farming

in Khorezm. Now the priority was to raise cotton yields and this was achieved by the increasing application of mineral fertilizers from 1935 onwards.

Sadly little was done to resolve the salinization problem.

|

Officials inspecting the Karakalpak cotton crop.

Image courtesy of the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

Massive changes were also being forced upon the social life of the people. After initial concessions to Islam after the Revolution, the early 1920s

saw the first Communist anti-religious campaign get underway across Turkestan. However while some Muslims were encouraged to join the Party, the

majority simply became more discreet in the way that they pursued their faith. In 1927 the Soviet government introduced the hujum, or

offensive, against all social practices considered to be oppressive to women, such as the marriage of under-age girls, the bride price, the tradition

of seclusion and the veil. In strictly orthodox centres like Khiva the seclusion of women was still strictly observed. Women's rights became

enshrined in law and various initiatives were launched to involve women in the social, economic and political life of their district. The veiling of

women was seen as the most overt symbol of female oppression, and women were encouraged to discard the veil. There were mass burnings of

paranjas in towns like Samarkand and Tashkent, resulting in a strong male backlash, with a few women being attacked and disfigured. However

in many cases these events were just a gesture; Party supporters took their wives to rallies to burn their veils and made them wear new ones the

following day! The main force of change was economic as women became increasing integrated into the workforce, so the old traditions became

increasingly eroded, especially in the urban areas.

Anti-religious pressure intensified during the 1930s, partly through a drive known as the Movement of the Godless. Muslims were showered with a

wave of propaganda and the Qur'an and the hajj to Mecca were both officially banned. Many mullahs were persecuted during the purges between

1932 and 1938; religious land was confiscated and mosques, medressehs and maktabs were closed. However it would have been provocative to

knock the old religious buildings down, so they were just left to decay. The teaching of religion had already been forbidden in state schools long

before compulsory primary education was introduced in 1930. The year before that had seen the introduction of the Latin alphabet, undermining

traditional religious teaching by outlawing the holy medium of Arabic. Of course Islamic belief continued, but increasingly in private, with unofficial

elders acting as mullahs at weddings and funerals. It became unwise to display strong Islamic beliefs publicly. Some men began shaving their beards

and moustaches and wearing neckties, while some women started to wear Russian costume and to leave their hair uncovered.

In the more remote areas there was more resistance to these pressures, especially in Khorezm and among nomadic tribes with a robust traditional

culture like the Turkmen, and officials were more willing to turn a blind eye. A Soviet ethnographical survey of the Khorezm oblast in 1954-56 showed

that many traditional customs were still alive, even at that late stage. It was ironic that at the time that the traditional way of life of the

people was being forcibly overturned, Soviet academics were beginning to venture out from Moscow and Leningrad to study their vanishing customs and

material culture. From the late 1920s onwards archaeologists had begun to investigate the many ancient sites across Khorezm, including Urgench.

The first historical and ethnographic expedition to Khorezm seems to have arrived in 1929, organized by academician Preobrazhenski for the Russian

Association of Research Institutes of Social Sciences, RANION, with Sergey Tolstov as one of its junior members. By 1931 a local ethnographic section

had even been established at the scientific research institute in To'rtku'l. Tolstov returned in 1932 as the head of an ethnographic expedition

organized by the Museum of the Peoples of the USSR, which lasted until 1934, a trip that convinced him that he was really onto something big. He

returned to Moscow to lobby for the resources required to put together a much more focused and long-term research project, which would become the

famous Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition. Tolstov headed its first field trip to Khorezm in 1937, commencing a programme of study

that would continue until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

|

Shımbay bazaar, possibly late 1930s.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

It is hard to judge the full effect that collectivization and all the other changes had throughout Khorezm as a whole. The published Soviet histories

of the region are silent on the matter, only being obliged to record the government's successes. They list the dates of decisions, decrees, congresses,

and conferences; they name the officials and party members involved; they list the openings of cotton depots, meat-packing plants, printing houses and

research institutes, even the opening of the Karakalpak State theatre in 1930! History was reduced to nothing more than a sequence of improvements,

all engineered by the regime on behalf of a thankful and adoring nation.

Some sense of the real history of the region can be gauged from piecemeal facts and the accounts of some of the people who lived through it, albeit in

an anecdotal way. Women who were taken out of the home to work in the cotton plantations experienced some of the biggest changes. Although this was hot

and tiring work, it gave women independence for the very first time, along with a social life and some private income of their own. While Westerners

complain that the Soviets destroyed the traditional culture of Khorezm, we have met elderly women who have told us that as young girls they had no

desire to stay in their homes to embroider and weave for their weddings. Another aspect that is overlooked is that although many tribal and clan

leaders were killed or removed during collectivization, these were not always popular individuals and local peasants were often relieved to see them go.

|

Komsomol Brigade named after the 16th anniversary of the October Revolution constructing the Qızketken canal.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis

Western travellers had not been allowed to visit Soviet Khorezm since the First World War, so independent accounts of life in the region during the

1920s and 1930s are scarce. We are fortunate to have one good first-hand report written by Lyman Wilbur, a young civil engineer from Idaho. In order

to fulfil the cotton ambitions of the 1929 Plan, the Soviet government were keen to increase the acreage of irrigated farmland throughout Uzbekistan

and had hired Wilbur as a consultant on a two-year contract, during which he was based in Tashkent. He and his companions undertook a survey of

Khorezm in the August of either 1930 or 1931, first travelling by train to Charjou and there embarking on a small paddle-wheel motorboat called the

Chaika (Seagull) to sail down the Amu Darya to Khorezm. On reaching Charjou they observed a modest amount of traffic along the river, with local

100-foot-long single-masted native skiffs powered by huge square sails ferrying timber, cotton, oil barrels and other goods into the port, along with

Khorezmian liquorice root destined for the USA. The Russians were now operating a number of small motorboats, like the Chaika, on the river and were

also constructing five tractor-powered dredgers along the riverbank. Wilbur also observed a large bucket excavator dredge. After leaving the

irrigated, mosquito-infested banks around Charjou, they travelled for two days through a landscape dominated by desert and rolling sand dunes, with

the sole exception of the small oasis town of Dargan Ata. As soon as they reached the very southern part of Khorezm they had their first encounter

with some of the region's many irrigation problems. Many of the canals were simply not deep enough, so although they could channel water from the Amu

Darya during the flood season, their bottoms were too high to capture water from the river during those times when the water level was low. At the same

time, the canals were silting up so quickly that the farmers spent most of their time clearing them out instead of farming the land. At Pitnyak most

of the irrigation depended on crude and inefficient shigir water wheels, driven by a blindfolded camel or donkey, which scooped up water in

ceramic jars.

During his survey Wilbur had ample opportunity to see the local people across Khorezm and painted a picture of a relatively stable, albeit poor

community, the only danger coming from banditry, especially from Turkmen tribesmen. He also noticed that there were considerable differences between

different towns and villages. For example in some towns the women wore elaborate headdresses and brightly coloured or brightly embroidered robes,

while in others the costume was exceedingly plain. It was the busy weekly bazaar when he arrived in Pitnyak and the men were dressed in robes and fur

hats while the women had ankle-length dresses that looked faded and dirty. Lyman Wilbur next visited Hazarasp, just a little way north of Pitnyak, and

found that most of the town was now built outside of the walls of the old city. His attempt to photograph the fruit sellers in one of the covered

streets was hampered by crowds of curious men and boys wearing immense woolly hats. From here he crossed the Amu Darya to Shoraxan and found that

the Russian engineers were having problems with their conservative Turkmen and Uzbek labourers. The Russians wanted to build long straight canals

instead of the sinuous winding canals that had been constructed by the local people in the past. But the labourers refused to work on them, believing

that water would not run in a straight line because it could "see itself" in the distance!

After paying a courtesy call to the Russian Governor in To'rtku'l, Wilbur crossed back to the left bank of the Amu Darya on the Chaika and sailed down

the Shavat canal to New Urgench, the capital of Khorezm, to be entertained by the Irrigation Department Office with a lavish banquet. Wilbur and his

colleagues now had exclusive use of a Renault "desert car", one of the half dozen automobiles in Khorezm at the time. The next day they drove through

the desert to Khiva, finding one village along the way engulfed in sand. In Khiva some of the mosques had already been commandeered for non-religious

uses, one having been procured as an artist's studio by a Russian painter. The local metal workers had already been collectivized and an individual

artisan could no longer sell his own goods. Instead of offering traditional items of carved brass they were now selling simple utensils made from

copper sheeting.

The second expedition from New Urgench was westward to the lands formerly irrigated by the dried-up Darya Lyk. Much of the land was polluted with

"black alkali", where the sodium carbonate (soda) in the soil had dissolved the humus. All the depressions were filled with stagnant water, providing

breeding-grounds for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. A subsequent trip to Dashoguz was more positive. The centre had the appearance of a boomtown, with

much construction underway on a new Russian quarter, and with a newly built flourmill and airport. However, because of the risk from bandits, they

needed an escort of three policemen to drive to Gurlen and rendezvous with their boat. Now they sailed further downstream, passing the Sultan Uvays Dag

and the ruins of Gyaur qala before pulling in at Qıpshaq. Wilbur describes this as an exceptionally dirty and disease-ridden town, where most of

the children had scalp, eye, or nose afflictions. The bazaars had little for sale other than melons. They stopped overnight at Taqıatas and were told

that tigers and wild boars could still be found in the jungle along the right bank. Arriving at Xojeli the next day, they found it as dirty and

disease-ridden as Qıpshaq and described it as having appalling poverty, being the poorest region they had seen in Central Asia. Even so, the town's

womenfolk were bedecked with nose ornaments and gaudy dresses. The region between Xojeli and Konya Urgench was absolutely barren, broken only by the

large cemetery of Mizdahkan, and Kunya Urgench was no more than a few mud houses beside the ruins of Gurganj.

They reached Shımbay by boat from Xojeli, passing by tree-lined canal banks, a pleasant contrast to the bleak deserts that normally lined the

river. During a stop for engine repairs Wilbur got the chance to visit some Karakalpak and Qazaq yurts. Shımbay was now the capital of the

Karakalpaks and was cleaner than most of the other towns they had seen. Some of the mud buildings had been whitewashed and others had glass windows.

There was even an electric lighting system in operation. From Shımbay they returned to the Amu Darya and then set course for the Aral Sea.

The surrounding land soon became swampy and the various delta channels began to diverge. The occasional yurt was the only sign of human habitation.

In the river the reed-beds became so thick that it was impossible to distinguish the water from the land and they had difficulty following the channel.

They finally arrived at the Aral seaport of Qantoz'ek that night, at the mouth of the Amu Darya, opposite the island of Tokmak Ata. At daybreak they

transferred to the ferry "Turkistan", fortunately just in time for its departure later that morning. There had just been a storm and the largest ship

on the Aral Sea, the "Kommune", lay in the outer harbour waiting for the rough seas to subside. The "Turkistan" had no more than ten deck passengers

and a few other cabin passengers on board and soon hit rough water, making most of the passengers seasick. The ship rolled and pitched to such an

extent that Wilbur had to hang on to his berth throughout the night, but by the following morning they were in the lee of the islands, including the

prison island of Vozrozhdeniye. They reached the port of Aralsk the following night, where they finally caught the train for their return to Tashkent.

|

|

Qayıqs on the Amu Darya, probably 1930s.

Images courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

Another rare Western visitor at this time was the black left-wing American poet, Langston Hughes, who spent one year in Soviet Central Asia between

1932 and 1933. He travelled from Ashgabat to Bukhara via Merv but unfortunately did not make a side-trip to visit Khorezm. Hughes had initially been

invited to Moscow to make an anti-American film, which then fell through, so as an honoured guest he headed instead for the USSR's equivalent of the

American cotton-growing south - Central Asia. He was predisposed towards the apparent equality of the Soviet system compared to the apartheid of

1920s America and commented favourably on Uzbekistan, especially the solidarity of the ordinary people. Of course he was carefully chaperoned during

his visit and was probably not an objective observer of what he saw.

The intrepid Swiss traveller Ella Maillart passed through Khorezm in 1932 on her journey through Turkestan, despite advice in Bukhara to avoid such

"savage regions". She left Charjou on an Amu Darya paddle steamer called the "Pelican", taking six days to reach To'rtku'l. A high-speed

"hydroglisseur" service was already doing the same journey in six-hours. Bales of Khorezmian cotton were being ferried upriver on square-sailed

qayıqs and Turkmen yurts were pitched along the riverbank. Interestingly, even at this late date, Basmachi bands were still causing problems

in the area. Maillart stayed in To'rtku'l for ten days at the home of a Russian official and was impressed with the place, considering it one of the

finest towns in the whole of Turkestan. She described it as "a land of milk and honey" since the markets had an abundance of meat, butter, and

vegetables and the baker had an abundance of bread. The Muslim population were still wearing their traditional costumes, although the young men were

clean-shaven. A small boat took her further downstream where she took an arba to New Urgench and the following day travelled on to Khiva.

Although the minarets and medressehs impressed, her overall impression was one of general decay and grimness and she was more impressed with a nearby

colony of Volga Germans.

Unfortunately with the onset of winter she was increasingly pressed for time and passed the rest of her time in Khorezm in a hurry. Thankfully she

took many photographs, leaving us a unique record of the life of the ordinary people of Khorezm at that time. Back on the Amu Darya she caught the

"Lastotchka" steamer to Qantoz'ek, from where she planned to cross the Aral Sea to Aralsk before the service was suspended in late November. When

they arrived at the large river port at Xojeli she discovered that the port on the Aral was already closed the last boat of the season, the

"Kommune" had sailed the day before. Unless she stayed for the winter, her only way home was overland. She took another arba to the small

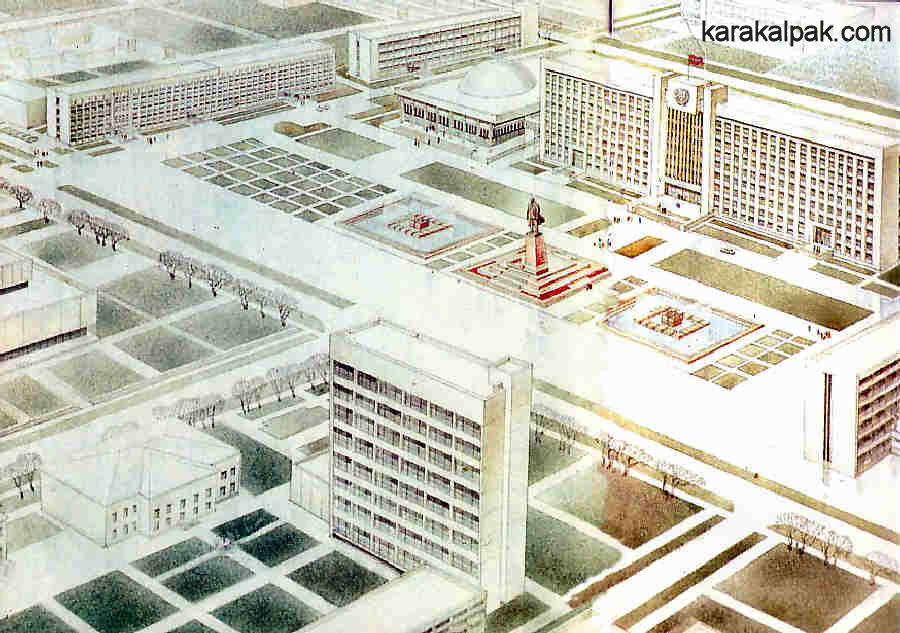

village of No'kis, where there was a shortage of accommodation. Workers were flocking into the village to work on a hospital construction project.

There was a rumour that plans had been made to build a new city there for 200,000 people. It was anticipated that much of To'rtku'l would soon be

swallowed-up by the Amu Darya and an alternative major centre of administration was required. People had been told that all the wood for the

scaffolding was to be transported from the Urals, crossing the Aral Sea by steamer. The whole of the next day was spent on the monotonously straight

road crossing the desert to Shımbay, where Maillart slept overnight in a yurt. The following day she set off with her guide on horseback to

reach Taxta Ko'pir where, with the exception of the main street, the houses were all built haphazardly and well apart from each other. With the

desolate flat horizon in the distance, she had "... an astonishing impression of having come to the ends of the earth". There, after six days of

trying, she finally joined a caravan of three camels loaded with grain for sale in Kazalinsk. They heading off through a landscape of stunted bushes

and well-worn tracks, dotted with yurts surrounded with tall bushes to provide shelter from sand and snowstorms. Travelling north they crossed

through the Qizil Qum with its saxaul covered dunes and takyrs of cracked clay, before reaching the open steppe and at last, after a journey

of two weeks, the Syr Darya. Throughout their journey they passed people travelling south towards Khorezm, seeking work, perhaps on the construction

of No'kis. These migrants clearly believed that the situation in Khorezm was a lot better than the one that they were leaving behind in Kazakhstan.

|

A stack of rotting cotton at Xojeli harbour, one of the consequences of collectivization.

Photographed by Ella Maillart in late 1932.

The bazaar at Taxta Ko'pir photographed by Ella Maillart in November 1932.

It has been said that the First Five Year Plan achieved one of the most precipitous declines of living standards in peacetime history. Although

Stalin was shaken by the national upheaval his policies had caused, he was unrepentant and publicly claimed his Plan had been a big success. At the

end of 1932 it was claimed that 99% of all Soviet industry was owned by the state and that 90% of the crop area was farmed by the collectives.

The Second Plan was purportedly aimed at the complete and final elimination of the remaining capitalist elements, emphasizing the need for quality

rather than quantity and on consolidating the improvements achieved so far. One of the successes of the Plan had been the establishment of universal

compulsory education and the development of a growing band of technicians and specialists. In the political field there was now an established system

of economic and political control, supported by a growing body of apparatchiks in the secret police, army, trade unions and Communist Party.

The period from 1934 to 1941 was one of consolidation for the totalitarian state, and began with a mass purge of the Party. The period was

characterized by accusations, arrests, show trials and confessions, some known to have been achieved through torture by the NKVD secret police. The

targets were senior party officials and old Bolsheviks, including the whole of Lenin's Politburo excepting, of course, Stalin himself. Many scholars

have attempted to rationalize the reasons for Stalin's terror campaign at that time he appeared to the outside world to be perfectly secure, since

most of his opponents had already been crushed and the Politburo was now solely composed of Stalin's own henchmen. Perhaps he was eliminating the

possibility of any future challenge - there were undoubtedly many dissenters throughout the Party, particularly following the disaster of the First

Plan. The elimination of a substantial proportion of the Soviet leadership certainly intimidated the rest and sent a clear message throughout the

USSR concerning the treatment of critics and dissenters. Within Central Asia many senior Communists were eliminated for failing to meet the

unrealistic objectives of the First Plan. Many more were branded "traitors" and "deviationists" during the later purges of 1937-38, including

Faizullah Khojaev, the Uzbek Prime Minister, and Akmal Ikram, the First Secretary of the Uzbek Communist Party, who were accused of a nationalist plot.

In the Turkmen SSR many thousands of Communist leaders were executed for nationalistic tendencies, including Kaikhaziz Atabayev, the Prime Minister,

Nedirbay Aytakov, Chairman of the Central Executive Committee, and Yakov Popok, First Secretary of the Turkmen Communist Party. From 1937 onwards

Kazalinsk on the Syr Darya became one of the places to which some of the luckier intellectuals were sent into exile. Until this so-called Great

Purge, many Communist leaders in Central Asia had been willing to allow the local people to continue enjoying many of their local customs. But now

such tolerance was dangerous.

|

|

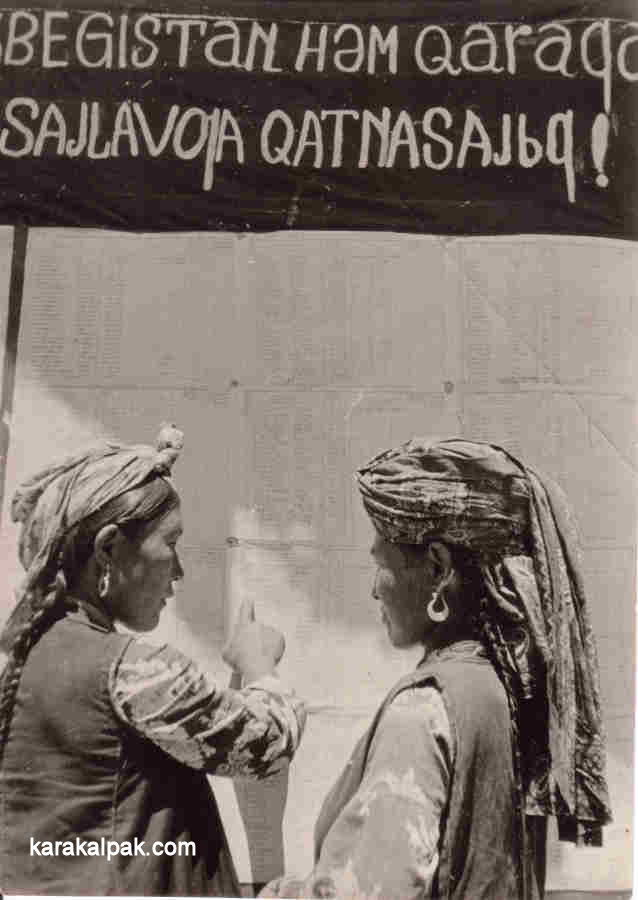

A woman and a group of young girls from the local Komsomol going to vote in 1938 at an election

at the kolxoz named after Kuybyshev in Shımbay region. Images courtesy of the Savitsky Museum, No'kis.

Karakalpak women checking the electoral register during elections, probably during the second half of the 1930s

The sign, written in Karakalpak Latin script, calls for full electoral participation. The photograph looks staged.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis

In 1938 Moscow issued a decree requiring that the Russian language be taught in all non-Russian schools. This was associated with a second