|

Contents

The Shayqalta

Geographical and Tribal Origin

Structure

Materials

Types of Shayqalta

Other Small Bags

Historical Background

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

References

The Shayqalta

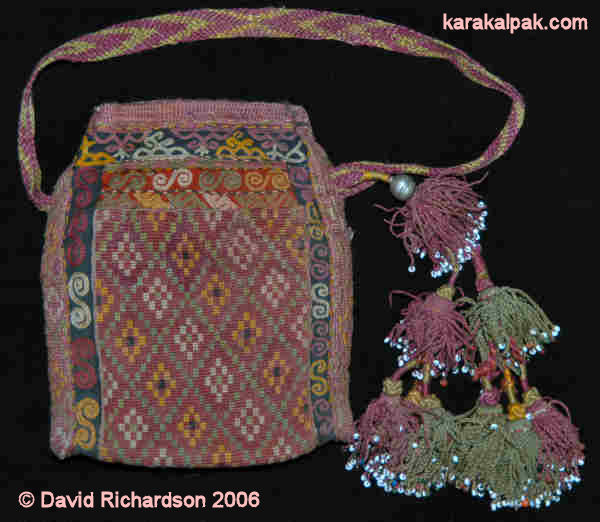

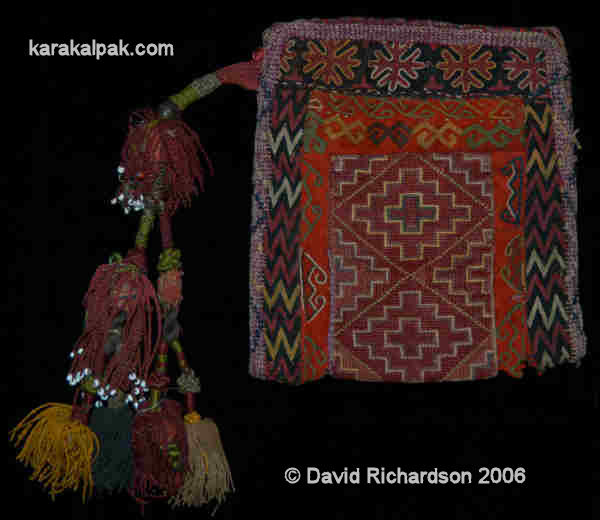

The Karakalpak shayqalta is a small cloth bag, usually rectangular in shape, lined with printed cotton, and open at the top.

It is colourfully decorated with finely executed silk embroidery and is usually edged on all four sides with raspberry red jiyek.

A long cord, decorated in red and green chevrons and terminating with a bunch of tassels, normally red and green, is frequently fastened to the upper

part of one side. Occasionally this is missing, or else the tassels are attached directly to the bag.

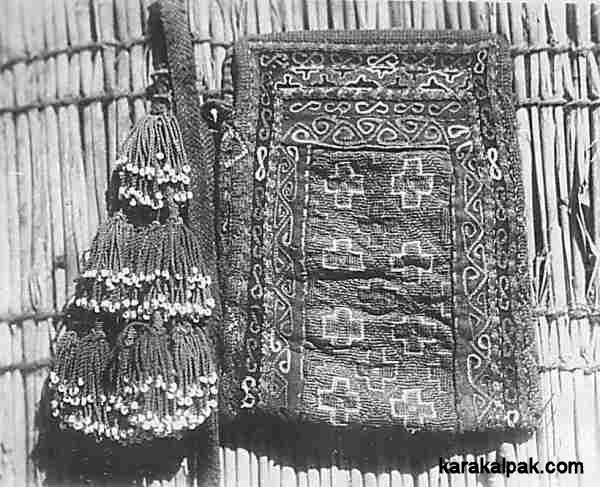

Karakalpak shayqalta held by the Savitsky Museum of Art, No'kis.

Shayqalta is simply Karakalpak for tea bag (шай қалта in Karakalpak),

qalta being derived from halta, the old Turkic word for a bag or small sack. Such bags are supposedly designed for

carrying dried leaf tea from a man’s waist belt, although every example we have examined shows little sign of any regular wear and no

indication at all of ever having been used for holding tea.

This is because what may once have been a utilitarian bag for holding tea had, by the early 20th century, been transformed into a symbolic

wedding gift. The dowry of every prospective bride included a shayqalta, lovingly embroidered as a present for her future husband and

traditionally handed over after the first night of the marriage. As such they were never regularly used or worn, other than at times of major

festivities. They seem to be found mainly among the northern Qon’ırat arıs.

They are an unusual item of Karakalpak male costume since embroidery hardly ever appears on men’s clothing and when it does it is usually

conservatively understated.

|

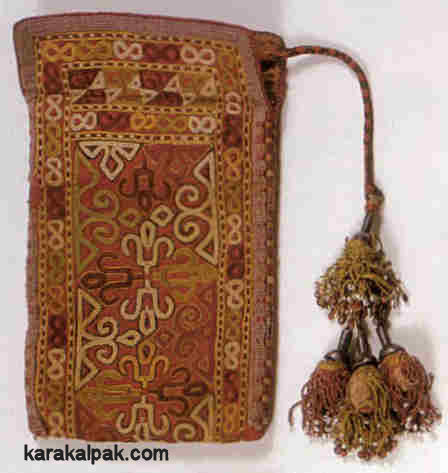

A Turkmen embroidered tea bag from the Russian Ethnography Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Of course, shayqaltas are not unique to the Karakalpaks. Somewhat similar bags are found among the neighbouring Uzbeks and Turkmen.

According to Anna Morozova, M.S.Andreyev (who collected items from Bukhara for the Uzbek State Museum of Art in 1936) reported that cross-stitch

embroidered bags were an obligatory part of Bukharan men's costume during the 19th century. They were hung from the waist-belt and were used

for keeping a comb, money and other small things.

Geographical and Tribal Origin

In June 2006 the Karakalpak State Museum of Art named after Savitsky kindly analysed their collection of 66 shayqaltas on our behalf, not

only according to design but also by the geographical region and the tribal affiliation of the former owners. This showed that they had originated

from all regions of the Aral Delta – Qon'ırat, Moynaq, Qarao'zek, Xojeli, Kegeyli, and No'kis city.

Unfortunately only 16 of the 66 had record cards indicating the tribal origin of their former owners:

| Arıs | Tribe |

Number |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıpshaq | 1 |

| | |

| Qon'ırat | Ashamaylı | 2 |

| Balg'alı | 3 |

| Baymaqlı | 2 |

| Qıyat | 5 |

| Mu'yten | 2 |

| Tog'ız Aq | 1 |

| Total | | 16 |

Interestingly 15 of these came from tribes and clans belonging to the Qon’ırat arıs and only one from the Qıpshaq tribe of

the On To'rt Urıw arıs. Of course the tribe of the owner is not necessarily the same as the tribe of the original maker, although

there is a good chance that they belong to the same arıs since the Qon'ırat live in the north of the delta and the On To'rt

Urıw in the south.

Structure

Shayqaltas vary considerably in length from 15½ to 23cm, and in width from 9½ to 16cm. The most common length is 18 to 19cm, and

the most common width is 15 to 16cm.

Over two thirds of shayqaltas were made specifically from scratch and their basic layout is fairly constant. They were made from a

rectangular piece of handwoven cotton bo'z, twice the length of the required bag. This was either plain or shatırash,

a finely checked cloth woven from alternating red and black warps and wefts.

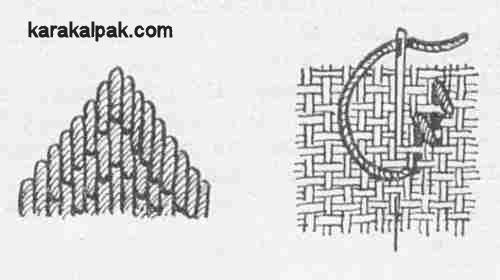

The first operation was to embroider the central field of the bag, using either cross-stitch or a form of satin-stitch known as teris qayıw

(meaning opposite or reverse side) stitch. The latter stitch is executed on the rear side of the textile. Once completed, the embroidered

field was bordered with narrow strips of contrasting qara and qızıl ushıga, the black cloth being used to form an

outer border around all four sides of the field and the red cloth used to form either a single inner strip at each end or occasionally a complete

inner border between the qara ushıga and the field. The ushıga borders and strips were then embroidered with rows

of simple repetitive motifs using chain-stitch, the joins between the central field and the strips of ushıga being concealed with rows

of coloured satin-stitch known as qa'wıp tigis or in rare cases with overstitching using gold metal-wound thread. The inner face of the bag

could now be lined with a similar sized rectangle of commercial printed cotton cloth, leaving the outermost edges to be finished, usually with a

border of plain raspberry red jiyek. In some cases however, threads of contrasting colour might be included to form a

patterned jiyek edging; in others the red jiyek might be patterned geometrically by means of overembroidery.

Standard layout of a Karakalpak shayqalta embroidered in cross-stitch.

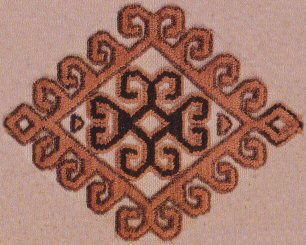

The qara ushıga is decorated with shiylawısh wood-plane motifs at the top and qumırısqa bel or

"waist-of-an-ant" motifs down the sides.

The Richardson Collection.

Now a length of narrow braid or tape was handwoven in warp substitution technique using a double set of red and green silk warps, thereby

creating an alternating pattern of red and green chevrons. One end of the tape was finished with a set of matching red and green tassels

often with small, predominantly white, beads at their ends.

The rectangular sides of the bag were then folded in half and sewn along two sides to form a bag. A gap of about 1 to 2cm was often left

at the top of each seam for ease of access to the contents of the bag. The tape and tassels were sewn to the top of the bag at one side.

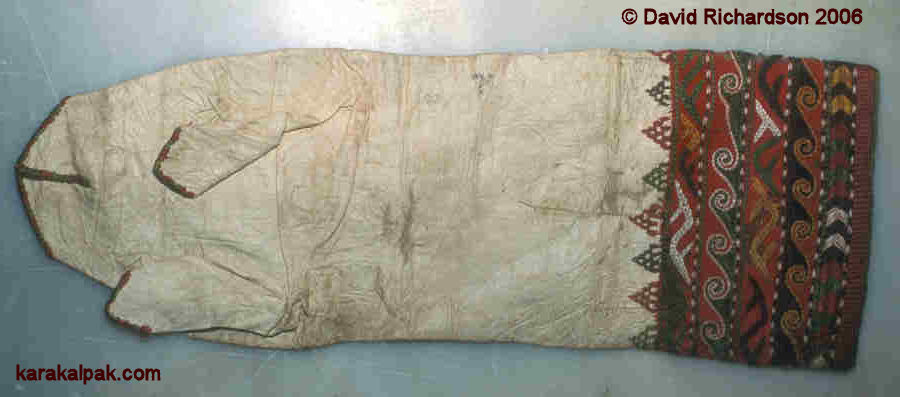

However not all bags were made in this fashion. Some were made utilizing sections of patterned embroidery recovered from previously used

items, for example from the orta qara (middle black) of a qızıl kiymeshek, the jag'a (collar) of

an aq jegde, or a section of jen'ush (sleeve cuff).

|

Karakalpak shayqaltas in chain-stitch come in a wide variety of patterns.

This one has a version of shayan quyrıq or scorpion's tail motif down the sides.

The Richardson Collection.

Several of the examples of this type that we have examined have strips of embroidered qara ushıga bordering the two long sides of the

embroidery fragment but not the ends, just like the example above. The two outer edges and sometimes the internal joins are then finished in strips

of red jiyek. The textile is then folded to form the bag, the unfinished ends being sewn to a separate cuff, which forms the top opening of

the bag. There does not seem to be any particular reason for this. The rough ends of the piece of orta qara could just as easily be covered

by an insert of embroidered ushıga as in the normal construction technique. The addition of the cuff (which obviously only has one

seam) means that a small gap can only be left on one side and therefore access to the contents of these bags is made slightly more difficult.

Materials

Bo’z

Karakalpaks used two types of cloth for embroidery. The first of these was a rather coarse handwoven cotton fabric called bo'z. This was

woven in plain cotton and could be dyed or left undyed. It was used for making children’s clothing, shirts, simple ko'yleks (dresses),

and for the aq jegdes and aq kiymesheks. Blue bo’z, known as matar by the Uzbeks, was used for ko'k ko'yleks

and jen'se (oversleeves). One form of bo'z was woven with finer spun cotton warps and wefts, which both alternated between sections

of red and black, resulting in a finely checked cloth known as shatırash.

Because of its coarse grid-like structure, bo'z lent itself to the embroidery of geometric patterns using cross-stitch. Meanwhile

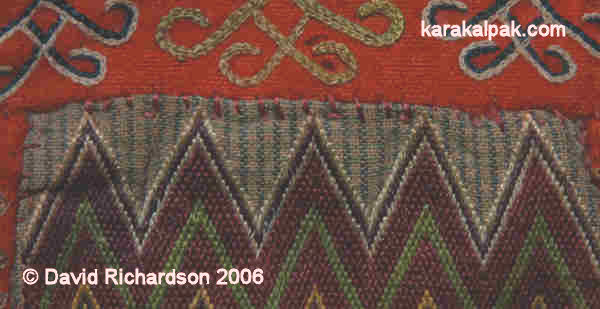

shatırash was particularly favoured for satin-stitch embroidery. In the example shown below the shatırash (checked)

bo'z is clearly visible above the silk embroidered ırg'aq (zig-zag) pattern.

The chequered shatırash exposed above the satin-stitch of the central field. The Richardson Collection.

Ushıga

The other fabric that was commonly used by the Karakalpaks was ushıga. This is a machine-made felted woollen broadcloth which was

highly prized by the Karakalpaks in the past. In its red form it was used to make the front of the qızıl kiymeshek.

Fragments of this cloth were put to a variety of uses; on duwashıq (amulets for the yurt door), on children's clothing, and so on.

It is therefore not surprising that scraps of this cloth featured heavily in these bags.

Over 60% of all of the bags we have seen have pieces of both qızıl (red) and qara (black) ushıga

inserted. Because the warps and wefts of the ushıga are concealed by the felting, the structure of this cloth lends itself to

free-flowing embroidery in chain-stitch.

Jiyek

The edges and sections of the bags were often finished with decorative strips of braid called jiyek, as were the sections on kiymesheks.

The initial appearance is of a separately made braid that has been attached to the edges and joins of the bag, but this is not the case. The

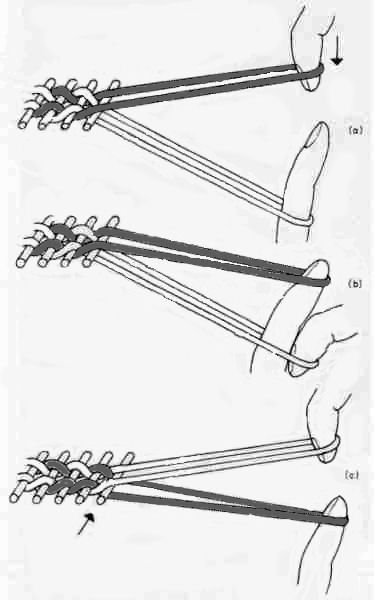

jiyek was directly woven onto the textile by means of a finger-weaving method called "warp-twining by loop manipulation" using sets of silk cords,

raspberry-coloured silk being the most popular, especially in combination with green.

It required two people to weave the jiyek. Firstly six, eight, or ten long loops of silk cord were attached to the edge of the

unfinished bag at a particular point by one of the weavers. The ends of the loops were held by the second weaver so that they passed around the

ends of her fingers, half of the loops on the fingers of one hand and half on the fingers of the other. The loop manipulation involved slipping

the loops from the fingers of one hand through the corresponding loops on the other hand, a dexterous weaver being able to do this for all pairs

of loops at the same time. To create the "braid" or jiyek, the first weaver would couch the first set of loops to the textile before the

first manipulation by passing a needle threaded with the base colour through the shed formed by the two sets of loops. As each subsequent manipulation

occurred a further couching thread was added. This thread effectively became the weft of the braid and was repeatedly looped over the edge of

the bag and then sewn back through from the back to the front to form the next weft. From the rear of the flattened-out bag this weft thread

appears like a coarse blanket stitch. Of course the latter was hidden internally once the bag was folded and sewn along its sides.

Warp-twining by loop manipulation, using just two loops.

From "The Techniques of Split-Ply Braiding" by Peter Collingwood. Image courtesy of Peter Collingwood.

Simple motifs, mainly half diamonds, could be created using different coloured threads. When the two edges of the piece of shayqalta were

brought together, these half diamonds would meet and form a whole diamond. As a short-cut some jiyek was woven in red silk and then

overembroidered with contrasting coloured threads using a loop-stitch to create simple geometric patterns.

Linings

Most shayqaltas are lined with machine-printed cotton. This was imported into Central Asia from Russia in increasingly large quantities

from the mid-19th century onwards. Over time the manufacturers changed their designs to reflect the taste of the local buyers. Red floral

patterns were especially popular. One favourite pattern was known as aydıllı and it is found on the backs of

kiymesheks, as the outer covering of shapans, and even as turbans. Some bags are lined with a mixture of several different

pieces, obviously utilizing every scrap of fabric available. A few bags are left unlined and some have a lining of Bukharan ikat.

Gold Metallic Thread

Although most stitching was done using silk thread, a few bags incorporate small amounts of gold metallic thread used either as highlights

on the bag itself or, more commonly, as a winding on the top of the tassels.

Gold thread work surrounding the qızıl ushıga panel of a

satin-stitch shayqalta. The Richardson Collection.

Types of Shayqalta

There are 3 main types of shayqalta:

1. Kerege Ko’z Pattern in Cross-Stitch Embroidery

These are by far the most common type of shayqalta, accounting for about 40% of all examples held by the Savitsky Museum. The central

field is embroidered with a diamond lattice using cross-stitch, or shırıs tigis. Karakalpaks call this pattern kerege ko'z nag'ıs,

meaning the eyes of the yurt lattice motif.

A kerege ko'z patterned shayqalta with stepped diamonds embroidered in cross-stitch.

The qara ushıga is decorated with a row of solaq motifs (part of a wooden cart) beneath the

qumırısqa bel motifs.

The Richardson Collection.

A kerege ko'z patterned shayqalta with crosses embroidered in cross-stitch.

In addition to qumırısqa bel, the qara ushıga is decorated with solaq and

qos mu'yiz motifs.

The Richardson Collection.

The elements of the design are small coloured rectangles of cross-stitch, so the lattice cells are in the form of stepped diamonds.

In some examples the cells remain empty, in others they contain either stepped diamonds or crosses, often arranged in alternating coloured rows.

Diamond lattice patterns are common in Karakalpak folk art. Similar embroidery patterns can be found in aq jegdes and on the front of

ko'k ko'yleks. Karakalpak master carvers often used lattice patterns on the front of sabayaq wooden chests, using two alternating

motifs without a central composition.

2. Ιrg'aq Pattern in Satin-Stitch Embroidery

The second group of shayqaltas all have a pattern known as ırg'aq (zigzag), consisting of parallel rows of coloured horizontal

zigzags on a red background. They are usually embroidered on shatırash bo'z using a reverse satin-stitch known as teris qayıw.

This literally means reverse side and was sewn working from the back side of the fabric. Small stitches are made very tightly together, parallel to

the warp of the backing cloth, covering it with the silken threads. The zigzag pattern is achieved by counting the weft threads.

A ırg'aq patterned shayqalta embroidered in satin-stitch. The Richardson Collection.

Almost 23% of the shayqaltas in the Savitsky Museum collection are of this type.

Illustration of the teris qayıw stitch from the front and the back. The Richardson Collection.

From Klavdiya Antipina, 1962.

According to Klavdiya Antipina the same stitch was widespread among both the northern and the southern Kyrgyz, although the number of items that

they embroidered with it was very limited. The Kyrgyz called the stitch terskaiuk. It was particularily associated with the Karakalpaks

in Central Asia and was also found among some of the peoples of the Volga region.

3. Decorative Patterns in Chain or Cross-Stitch Embroidery

The third type of shayqalta has a central field of ushıga, generally decorated in chain-stitch or ilme, but

occasionally in cross-stitch. However on closer examination these are virtually all made from fragments of embroidery recovered from older

female garments, the most frequently occurring item being a chain-stitch fragment from a qızıl kiymeshek aldı:

A chain-stitch shayqalta based on a fragment of orta qara from a kiymeshek.

The central field is qoralı gu'l or fenced flower. The Richardson Collection.

Other sources include aq jegde jag'a, aq kiymeshek aldıs, and jen'se made from blue bo’z.

A cross-stitch shayqalta based on a fragment of an aq jegde. The Richardson Collection.

Some 21 of the 66 shayqaltas in the Savitsky Museum, or 32%, are of this type. Of the 21 examples, 19 are made from qızıl

kiymeshek fragments, one is from a jen'se and another is from a jen'ush.

It seems that a different social tradition may have come into play with these examples. It is unlikely that a young bride-to-be would

give her fiancé a tea bag made from a piece of an old woman’s garment such as an aq jegde. We know that when a woman died her clothing

was sometimes cut up and pieces were given to relatives as a keepsake. If she had lived to a great age or had had many children it was

considered especially lucky to have such a token. Perhaps tea bags were made from some of these pieces as a memento or perhaps they are

another illustration of Karakalpak thrift, ensuring that every scrap of old embroidery was recycled in an acceptable form.

However not every bag of this type was made from recycled embroidery. We are aware of a couple of exceptions. One example in our own

collection has been specifically made from scratch with a central field of ushıga embroidered in chain-stitch. The field appears to

be like a "sampler" for an orta qara. It is clear from the execution of the corner pattern that this has been conceived as a piece in its

own right. The shatırash bo'z lining is again clearly visible and the top third of the bag has been lined with a nice strip of silk ikat

in harmonious colours.

|

A rare chain-stitch shayqalta that does not include any recycled embroidery. The Richardson Collection.

Unfortunately in recent years unscrupulous local Karakalpak dealers have begun making up new shayqaltas from embroidery fragments to

sell as souvenirs to unsuspecting tourists.

Other Types

A few shayqaltas do not conform to any of the above three categories. A small number occur with a plain central field, devoid of

embroidery. One beautiful example made from a rectangle of green velvet is on display at the Moscow State Museum of Oriental Art.

The Savitsky Museum has another made from Bukharan padshai (half silk, half cotton) ikat.

A simple shayqalta with a central ikat field. Savitsky museum, No'kis.

One very rare type is a rounded bag with a central field of qara or qızıl ushıga embroidered

with mu'yiz (horn) motifs in chain-stitch. In one example the black field is surrounded by a red border:

A rare round-shaped shayqalta with mu'yiz and shiylawısh motifs.

The Richardson Collection.

A second example from the Savitsky Museum has a red field with a narrow border of black.

A rare round-shaped shayqalta with similar motifs and a fine edging of

patterned jiyek.

Image courtesy of the Savitsky State Museum of Art, No'kis.

Other Small Bags

Pul qalta

The Karakalpak pul qalta or money bag is a mystery. Anna Morozova noted that there were two types of festive bags – a pul qalta

for money and a shayqalta for tea. Both were an obligatory part of male costume in the rural areas and both were usually embroidered by

girls to present to their husband after the first night of marriage. However we have never seen such an item and no examples exist in the Savitsky

Museum

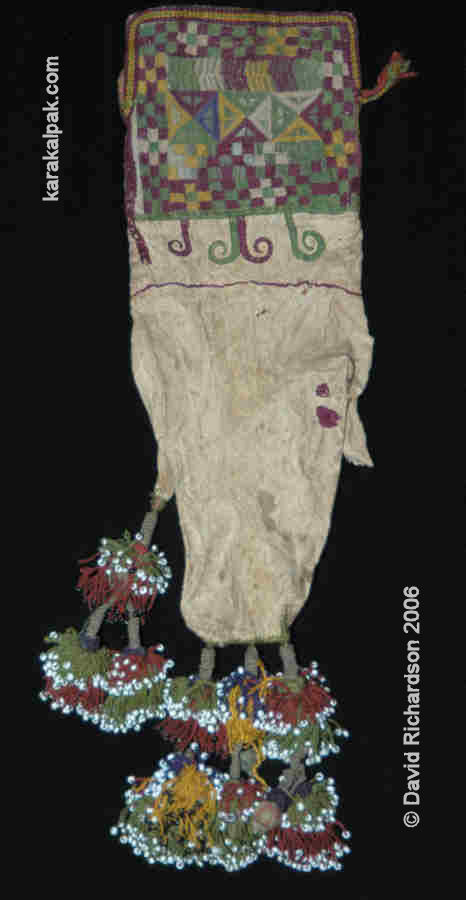

Tarı qalta

Another rare item was a small millet bag or tarı qalta for holding snacks of millet or ground millet mixed with butter and sugar,

which were consumed as an accompaniment to tea. According to the curators at the Regional Studies Museum in No'kis these small bags were made from

the skin of a small mammal, such as a hare. However the original inventory card of an example kept in Tashkent (see below) records that it was made

from the skin of an unborn goat. They were decorated with a band of embroidery around the neck and with clusters of tassels suspended from the ends

of the short legs. Some had a cord and tassels attached to the top, just like a shayqalta.

Tarı qalta with green and purple qos tigis or double-stitch embroidery. The Richardson Collection.

One example is displayed at the Regional Studies Museum in No'kis where it is referred to as a shanash, which simply means a small bag. A 2004

museum brochure refers to the same item as "a bag for crumbly things":

Tarı qalta.

Image courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

A second example has been on display at the Islam Khoja Medressa in the Ichan qala in Khiva.

Two others are held by the Samarkand State Museum, which attributes them as early 20th century choi-kaltas from Khiva. The embroidery on these

examples appears to be Turkmen.

Tarı qalta-like bags from Samarkand Museum.

Another simpler example, inventory number 1304 1-128, listed as a "calf skin bag with embroidered top" appears in the State Museum of History in

Tashkent. Its record card describes it as a shayqalta, collected in 1946 from No'kis and Shımbay, and made from the skin of an

unborn goat. The inventory number and date suggest it was collected in Karakalpakstan by G. Mirgiyazova.

Tarı qalta collected from No'kis/Shımbay in 1946 with a solaq motif.

Image courtesy of the Uzbek State Museum of History, Tashkent.

Some of these bags were owned by Karakalpak people, but the embroidery style is not typically Karakalpak and it is possible that they were

made by neighbouring tribes like the Turkmen or Khivans.

Temeki qalta

We have not yet seen a Karakalpak tobacco bag. Xojamet Esbergenov noted that the Khorezm Expedition acquired one example in 1973, which was

made of calf skin. The original owner claimed at the time that it had been made five generations ago.

Shınıqap

A shınıqap is a leather case for transporting and protecting one or more ceramic tea cups. It has a semi-spherical lid

which is fastened to the body of the case with narrow straps. Such cases were often decorated with copper wire and tassels made from thin

strips of leather, while others were embroidered. Xojamet Esbergenov claimed that they were one of the items found on a man’s waist-belt.

However they are quite heavy and bulky items and were more likely to be attached to a horse’s saddle than to a waist belt.

Mirror Bags

The final small bag found among the Karakalpaks is the mirror bag. However since this is an item for women rather than men it is covered under

Female rather than Male Costume.

Historical Background

Early nomads wore an open tunic fastened around the waist with a belt. Anything they wished to carry had to be suspended from their belt or

carried on their horse. For example, depictions of Massagetae warriors on the Apadana at Persepolis (dating from the 5th century BC) show them

wearing narrow belts with holders for their short akinakes swords suspended from a pendant. Golden vessels dating from the 4th century BC

recovered from kurgans north of the Black Sea show that the Scythians wore similar belts from which they suspended a gorytus, or bow case and

quiver. Actual belts ranging in width from 2.7 to 4.5cm were excavated from the Pazyryk tombs in the Altai, recently dated by dendrochronology

to the 3rd and 4th centuries BC. They were decorated with sinew and had pendant straps for holding a quiver, dagger, or short sword. Some had

silver or bronze plates. Leather purses and pouches were also found in some of the kurgans, one pouch being found inside a small leather saddle bag.

A very refined small leather pouch with a flap was discovered among some torn clothing. The flap was decorated with leopard’s fur and trimmed

with a border of red felt.

Belt buckles have been recovered in extensive numbers from kurgans across western Central Asia, indicating that many pastoral nomads wore

belts with buckles at the start of the Kushan era. Excavations of contemporary Hsiung-nu kurgans in northern Mongolia show that the early Huns

also wore belts decorated with buckles and plates. The belt was an important indicator of status among many of the cattle-breeding nomads

of Eurasia.

Sogdian murals show that by the end of the 5th century AD aristocratic men were wearing belts of two types: sashes of cloth knotted at the front

and leather belts decorated with metal plates fastened at the side. However after the establishment of Turkic political domination in the middle

of the 6th century, a new fashion appeared in which belts were decorated with rows of round and/or semicircular plaques. The belts also had short

pendant straps for fastening different accessories. Such Turkic types of belt were not often depicted in Sogdian art but from the frequent

archaeological finds of such belt plates we can assume that the distribution of such belts was common. As the Turks increasingly settled across

Central Asia they integrated with its indigenous populations and influenced their cultures.

Alabaster ossuary from Toq qala in the Aral delta, late 7th or early 8th century AD, showing Turkic tunics with lapels and belts.

Courtesy of the Savitsky Museum of Art, No'kis.

Belts remained an important status symbol under the Mongols. The Italian Franciscan Giovanni del Pian di Carpini attended the coronation of

Güyüg in 1246 and observed that among the many gifts bestowed by the foreign envoys there were "girdles of silk threaded with gold".

Known by the Mongolians as altan büse, these golden belts were routinely given to members of the Mongol court. According to

Rashid ad-Din, the Il-Khan Ghazan bestowed "fifty bejewelled belts and three hundred gold belts" on his retainers. Meanwhile Friar Odoricus of

Pordenone who travelled to the Yuan court in Beijing in the 1320s noted that the Khan's courtiers "are girt with golden girdles of halfe a foote

broad". Many fine gold and silver buckles and belt plates have been recovered from excavations across the former territories of the Golden Horde.

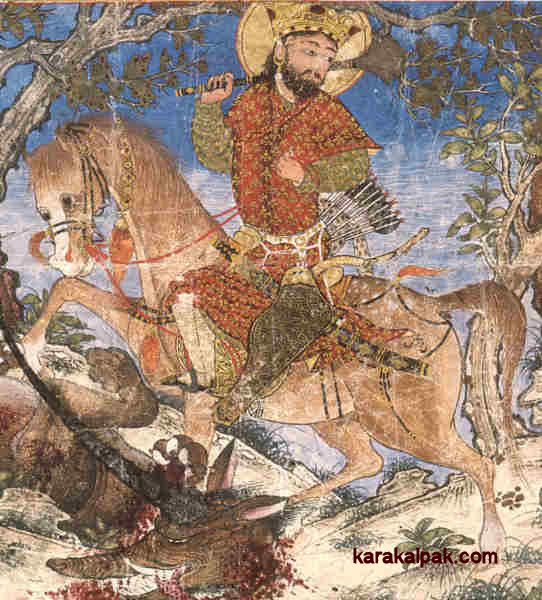

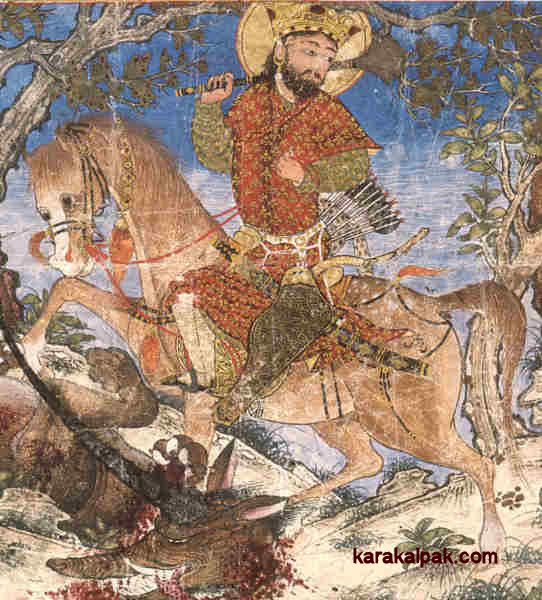

Illustrations of Mongols in Persian miniatures and from ancient manuscripts of Rashid ad-Din show belts decorated with metal plates and with pendants

supporting swords or quivers. A few show belts supporting small, possibly leather, pouches. Of course none of these references relate to ordinary

nomads or their local tribal leaders.

|

A belted Bahram Gur with purse, fighting a wolf, Mongol Iran (possibly Tabriz), 1330s.

From the Shahnama or Book of Kings, Harvard University Art Museum, Cambridge, Mass.

Mongol mounted archer with belt and purse by Mohammed ibn Mahmudshah al-Khayyam, Iran, 15th century.

From the Diez Albums, Staatsbibliothek, Berlin.

The first reference to Karakalpak costume was recorded in 1740 by Ivan Muravin, the surveyor of Lieutenant Gladyshev's expedition to Khiva and

the Aral region. Muravin noted that in general the costume of the Lower Karakalpaks, the Qazaqs of the Lesser Horde, the Aral Uzbeks, and the

Khivan Uzbeks was all very similar.

Regarding the Qazaqs he recorded:

"they gird themselves with belts cut from red leather, or whatever is available, the width is two vershok [equivalent to 9cm] or smaller; and on

those belts are fixed metal plates, and to the plates were fastened leather bags for storing bullets and gunpowder, and on other plates only a

small strap and a big bag in which they keep flint with a steel and other necessities: they call this an uzbelik; and when they are not on

ceremony they wear a simpler one [belt]."

The term uzbelik is not precisely defined but seems to refer to the whole belt assembly. Regarding the Karakalpaks, Muravin simply noted that

they wore the same dress as the Qazaqs, although they did not have belts made of red leather other than for their tribal nobles.

Such belts with pouches must have been widespread across Central Asia. In September 1770 Johann Peter Falk, Johann Georgi, and Christoph

Bardanes visited the temporary camp of Sultan Nur Ali, the grandson of the Khan of the Lesser Horde Abul Khayr. In his descriptions of the

Qazaqs, published seven years later, he noted that several of them wore a belt to which was always attached a sabre, a tobacco purse, a pipe,

a lighter, and a knife.

Qazaq man with leather belt and pendants holding a knife sheath, leather pouch, and container.

From Gustav-Fedor Pauli's "Description ethnographique des peuples de la Russie, tom 1", Saint Petersburg, 1862.

In 1819 Captain Nikolay Muravyov recorded that the Khivans were very expert at making up silk waist girdles. Meanwhile Khivan traders were

importing silk waistbands from Bukhara.

Arminius Vambery, describing the dress of the Central Asian male in his "Sketches of Central Asia" published in 1868 wrote that:

"Among the men, various objects of ornament are seen, those which hang from the Koshbag, such as good knives with silver or other

ornamented handles, gold embroidered bags for tea, pepper ans salt; ... "

The American Eugene Schuyler, travelling in Turkestan in 1876 observed that:

"The usual girdle is a large handkerchief or a small shawl; at times a long scarf wound several times tightly round the waist ... From the girdle

hang the accessory knives and several small bags and pouches, often prettily embroidered, for combs, money, &c… …tobacco, if the user can afford

it, is carried in a small bottle of Chinese jade or nephrite, but more usually in a very small gourd fitted with a stopper".

Henry Lansdell writing in 1882 described a similar belt worn by the Qazaqs:

"[He] is proudest of his girdle, often richly covered with silver, and from which hang bags, and wallets for money, powder, bullets, knife,

and tinder box, or flint and steel, the whole apparatus being called kalta".

Similarly the Danish explorer Ole Olufen wrote:

"The Bokharan man often carries a real arsenal of different objects suspended by a leather strap round his waist under his lungi,

such as purses for tobacco, money, the indispensable razor for shaving his head, and the nomads especially are always furnished with

tinder-box, awls, hammer, powder, shot-bags, whetstone etc."

The Europeans and Russians who visited the Aral delta shortly after the Russian conquest of Khiva in 1873 left us only glimpses of

Karakalpak dress at that time. For example Nikolai Karazin visited a small awıl in the northern delta along the road from

Qusxanataw elevation to Shımbay.

"But here the inhabitants of the village dared to approach us. There were eight men; only two of them were in khalats, the rest of them

were in the long shirts of rough white cotton fabric; these shirts were not belted and they delineated the thin, bony body ... They were all

in the inevitable huge black caps;"

Our best understanding of Karakalpak waist belts towards the end of the 19th century comes from surveys of elderly people conducted by

Russian and Karakalpak ethnographers in the 1940s. Xojamet Esbergenov has summarized the results, reporting that men wore either a

knotted sash, called a belbew, made from a cloth or kerchief, or a narrow leather belt called a qayıs.

A wealthy man or a bridegroom might wear a belbew made from a tu'rme or ma'deli woven in a Khivan silk-weaving workshop.

High-status belts could be woven from cotton, silk, or wool (pota belbew), made from hard leather (ka'ma'r belbew) or from

soft leather (degment belbew). These were generally embellished with ornamented metal plates and lined with bo'z.

One type of qayıs was made with leather pendants for suspending attachments. They were worn by working men, not for status or for

festivities. The accessories could be in the form of specialist hunting equipment such as an oq-shontay or pistol and bullet case,

a cap for a sparrow hawk, or a flint with a fire-steel. Alternatively they could be everyday items such as a qınap or sheath for a knife,

a shaqsha or horn tobacco box, a temeki qalta or tobacco bag, and a shayqalta or tea bag. The general impression is

that such leather belts were more common among the nomadic Qazaqs than the more settled Karakalpaks.

The most frequent accessory for a Karakalpak man was undoubtedly his shayqalta. The Karakalpak scholar Ag’ınbay Allamuratov researched

Karakalpak embroidery among local people in the 1970s and concluded that the shayqalta had once been a very common item on men’s waist-belts.

Karakalpak men carried tea and sugar with them, which they then presented to their hosts when visiting their houses. In the first decades of

the 20th century they were embroidered by girls before their marriage as a love token for their prospective husbands.

Karakalpak man wearing a ma'deli belbew.

From Aleksandr Melkov's "Album", photographed in 1928.

Courtesy of the Karakalpak branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences, No'kis.

Photographs taken by Aleksandr Melkov in 1928-29 and by Ella Maillart in 1933 support some of these conclusions. In these photos the majority

of men with belts were using a knotted kerchief or cloth and the others were using narrow leather belts and buckles. None of the pictures show

any items suspended from these belts. Although Melkov did not photograph the shayqalta in use he did capture the image of one cross-stitch

shayqalta in the kerege ko'z pattern on the background of a shiy mat:

Black and white photograph of a kerege ko'z shayqalta in cross-stitch.

From Aleksandr Melkov's "Album", photographed in 1928.

Courtesy of the Karakalpak branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences, No'kis.

Anna Morozova believed that the wearing of ka'ma'r leather belts with metal buckles had died out by the 1920s. From our own records we know

that shayqaltas were still being made during the 1920s, but it seems that by then they were no longer a practical item. They were not only

made by a young prospective bride for her groom but were also frequently made as general gifts for men.

Illustration of a shayqalta made from a chain-stitch qızıl kiymeshek.

Collected by ethnographers from the Khorezm Expedition from Qarao'zek region in 1948.

By the 1930s the Karakalpaks were increasingly coming under Russian influence, abandoning their traditional customs and culture.

When Tatyana Zhdanko and her team of ethnographers arrived to study Karakalpak life at the end of the Great Patriotic War they found

that shayqaltas were no longer made, although many families still kept them as mementoes of the past.

Pronunciation of Karakalpak Terms

To listen to a Karakalpak pronounce any of the following words just click on the one you wish to hear. Please note that the dotless letter

'i' (ı) is pronounced 'uh'.

References

Allamuratov, A., Karakalpak People's Embroidery [in Russian], No'kis, 1977.

Allsen, T. T., Commodity and exchange in the Mongol empire, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997.

Andrianov, B. V., and Melkov, A. S., Forms of Karakalpak National Ornament [in Russian], Archaeological and Ethnographical Works

of the Khorezm Expedition, Volume 3, Materials and Research on Karakalpak Ethnography, page 411 onwards, Academy of Sciences of

the USSR, Moscow, 1958.

Antipina, K. I., Special Material Culture and Applied Arts of the Southern Kyrgyz [in Russian], Published by the Academy of Sciences

of the Kyrgyz SSR, Frunze, 1962.

Collingwood, P., The Techniques of Tablet Weaving, Robin & Russ Handweaving, Inc., Oregon, 2002.

Dawson, C., The Mongol Mission, Sheed and Ward, London, 1955.

Georgi, J. G., A Description of All the Nationalities that Inhabit the Russian State [in Russian], Volume 2, Saint Petersburg, 1776 to 1777.

Gladyshev, D. V., and Muravin, I., Journey from Orsk to Khiva and back, completed in 1740-1741 by Lieutenant Gladyshev and

Geodesist Muravin [in Russian], Published by Khanykov, Saint Petersburg, 1851.

Lansdell, H., Russian Central Asia, Houghton, Mifflin and Co., Boston, 1885.

Maillart, E., Collection of Photographic Negatives, Elysée Photo Museum, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Mirsadiyeva, L., Maverannahr Suzanis, in A World of Oriental Carpets and Textiles, Published by the ICOC, Washington, 2003.

Morozova, A. S., The Domestic Cultural Life of the Karakalpaks at the beginning

of the twentieth century [in Russian], Doctoral Thesis, Department of History, Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR, Tashkent, 1954.

Olufsen, O., The Emir of Bukhara and His Country, William Heinemann, London, 1911.

Rudenko, S. I., Frozen Tombs of Siberia, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London, 1970.

Rusyaykina, S. P., Museum Funds as a Source for the Atlas of Central Asia [in Russian], pages 36 to 85, Materials on the Historical-Ethnographic

Atlas of Central Asia and Kazakhstan, edited by Zhdanko, Moscow-Leningrad, 1961.

Savitsky, I. V., Carving on Wood, Applied Arts of the Karakalpak People [in Russian], Published by "Science", Tashkent, 1965.

Savitsky, I. V., State Museum of Art of the Karakalpak ASSR, album [in Russian]. Moscow, 1976.

Schuyler, E., Turkestan, Notes of a Journey in Russian Turkestan, Khokand, Bukhara and Kuldja, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London, 1876.

Vambery, A., Sketches of Central Asia, Wm. H. Allen & Co., London, 1868.

Yatsenko, S A., The Late Sogdian Costume (the 5th to the 8th century AD), Webfestschrift Marshak Ērān ud Anērān,

Studies presented to Boris Ilich Marshak on the occasion of his 70th Birthday, edited by Compareti, Raffetta, and Scarcia, Libreria Editrice

Cafoscarina, Venice, 2006.

Zhdanko, T. A., and Esbergenov, X., Ethnography of the Karakalpaks [in Russian], Fan Publishing, No'kis, 1980.

Visit our sister site www.qaraqalpaq.com, which uses the correct transliteration, Qaraqalpaq, rather than the

Russian transliteration, Karakalpak.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|

|